Every year, a bunch of different studies come out that crown a winner, the “best network” in the USA. Each study claims to use the best, most scientific methodology to give “unrivaled accuracy” or “undisputed results,” or something else equally quotable.

But if the studies are so good, why do they give such different results? Take a study published today by RootMetrics, which has Verizon in first place and T-Mobile in last. That’s in stark contrast to a study last month from OpenSignal, which had T-Mobile and Verizon tied for first and Sprint languishing in last place.

The reason for the difference is that measuring cellphone networks is hard. We’re talking about trying to quantify a network that stretches across the entire country, works on tens of thousands of different devices and in all kinds of terrain. Trying to measure that, assign each of the big four wireless networks an easy-to-understand score and publish results in a 300-word blog post is basically impossible.

RootMetrics and OpenSignal are two good examples of the most common approach to actually measuring network signal and speed (as opposed to something like Nielsen, which surveys users for their perception of their network). RootMetrics buys devices and sends testers out to set locations, where they test all the networks head-to-head and record the results.

It’s known in the industry as drive-testing, and has some major advantages: it pits the networks head-to-head, it’s repeatable, and by controlling the number of tests, the location, and the testing device, you remove most of the variability in the testing.

OpenSignal takes a completely different approach. Rather than sending employees out with test devices, it encourages users to download an app. Users then conduct speed tests and coverage tests as they go about their day-to-day lives, and the data is uploaded to OpenSignal.

Compared to drive-testing, it’s less repeatable and less “scientific.” But it also has the advantage of sheer numbers: hundreds of thousands of OpenSignal users submitted billions of data points for their last test. That means OpenSignal is more likely to be representative of day-to-day performance of a network, as it’s measuring the actual day-to-day performance of users — not a statistical representation of the average day.

Yes, there are flaws in OpenSignal’s methodology too. Users are more likely to be on a network that works in their area, so you’re less likely to get data from areas that have no coverage. If a small town somewhere only gets Verizon signal, then everyone in that town is going to be on Verizon, and you’re not going to get a bunch of tests that show no signal for T-Mobile.

There’s also questions about demographics: wealthier people with nicer smartphones are more likely to be on expensive networks like Verizon and AT&T, which means more Sprint and T-Mobile users would be on older smartphones, which in turn are slower than newer devices on the same network.

The end result is that no one method is perfect, and it’s important to look at a range of results rather than just one test. For the majority of users, I tend to suspect that crowd-sourced testing like OpenSignal will be more representative, but without seeing the precise data set and methodology of all the studies (for example, the RootScores that RootMetrics provides are calculated using a proprietary algorithm) it’s difficult to make a call one way or the other.

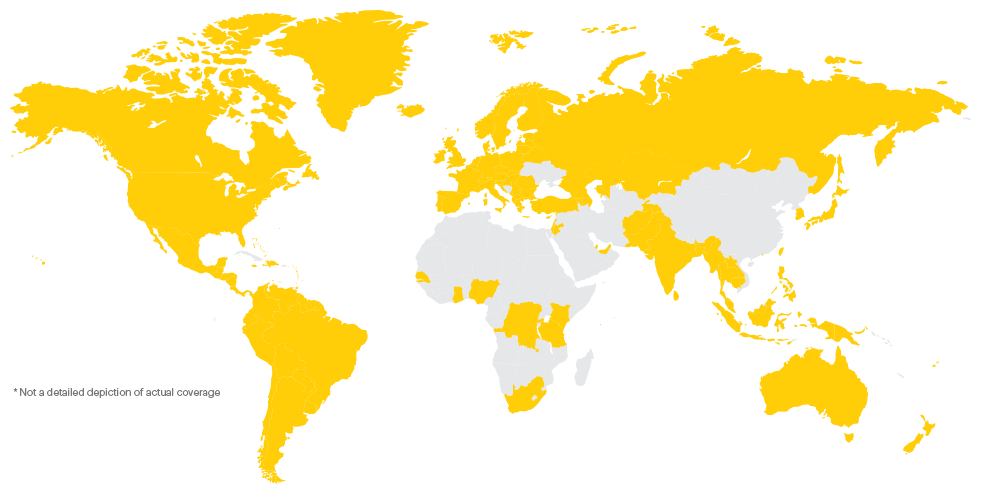

There is one thing that prospective customers can check, though: local coverage maps. Quantifying a cell network across a country is hard, but getting data on coverage on a particular street is comparatively easy. OpenSignal excels at this, thanks to the crowd-sourced data, and its coverage map should be the first thing you check when you’re thinking about switching networks.