- A tiny exoplanet-hunting satellite called ASTERIA managed to spot a distant world twice the size of Earth.

- The satellite detected the scorching hot world 55 Cancri e.

- In the future, microsatellites may play a more important role in planet-hunting.

It wasn’t that long ago that astronomers could only dream of having the technological might to peer into the cosmos and find new planets. Today, exoplanet discoveries come at a fast and furious rate, and now a ridiculously tiny piece of hardware called ASTERIA managed to spot a distant world as it orbited Earth.

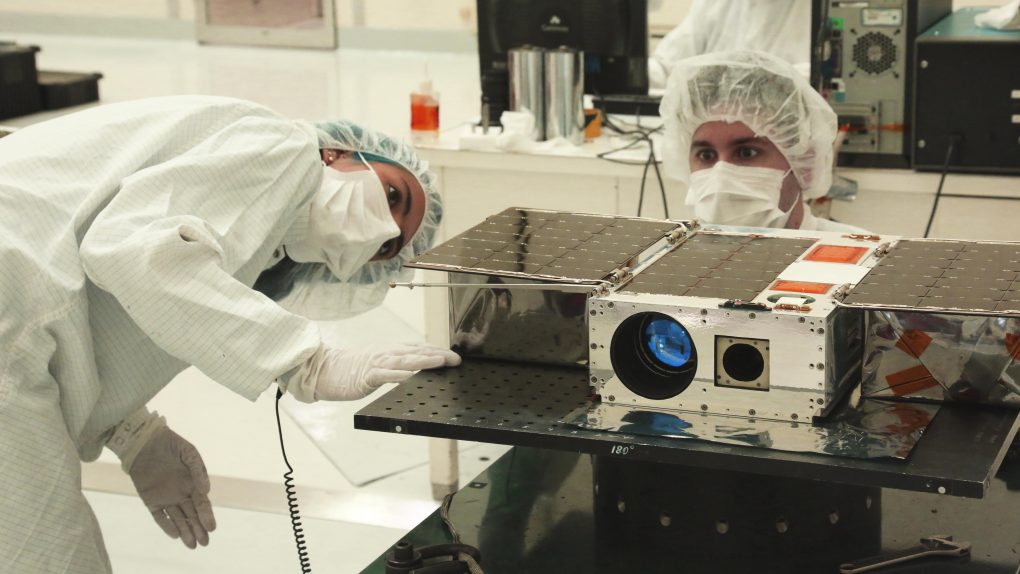

ASTERIA is microscopic in satellite terms. It’s only about the size of a briefcase, according to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, but that hasn’t hindered its ability to make groundbreaking discoveries. The planet it spotted is an ultra-hot world known as 55 Cancri e, and no, you wouldn’t want to visit.

55 Cancri e is considered a “Super Earth” because it’s rocky like our home planet but significantly larger. It’s estimated to be around twice the size of Earth, and over eight times as massive. That might sound appealing, at least until you see how close it orbits its star. The planet has a very close relationship with its star, and an entire year for 55 Cancri e passes by in less than one Earth day.

The planet was first detected back in 2004. ASTERIA wasn’t the first to spot it, but the fact that it managed to do so is nonetheless impressive. Like other exoplanet-hunting efforts, the satellite watched for subtle dips in the brightness of the host star in order to detect a planet passing between the star and Earth. The fact that it did this using technology shrunken down to the size of a briefcase is a serious achievement.

“Detecting this exoplanet is exciting, because it shows how these new technologies come together in a real application,” Vanessa Bailey of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory said in a statement. “The fact that ASTERIA lasted more than 20 months beyond its prime mission, giving us valuable extra time to do science, highlights the great engineering that was done at JPL and MIT.”

The ASTERIA project is itself quite unique, as it was part of a new JPL program:

ASTERIA was developed under JPL’s Phaeton program, which provided early-career hires, under the guidance of experienced mentors, with the challenges of a flight project. ASTERIA is a collaboration with MIT in Cambridge; MIT’s Sara Seager is principal investigator on the project. Brice Demory of the University of Bern also contributed to the new study.

Going forward, exoplanet detection will only continue to improve. As telescope hardware becomes more advanced, we’ll learn about new worlds on an even more regular basis. It’s an exciting time to be a space fan.