Of all the things that could make or break the potential for a world to support life, liquid water is one of the biggest. If a planet is devoid of water, or if that water is entirely locked away as ice, odds that life has taken root there drop dramatically. Earth has plenty of water, but we’re learning more and more that other locations in our solar system also hold liquid water, and sometimes in vast amounts.

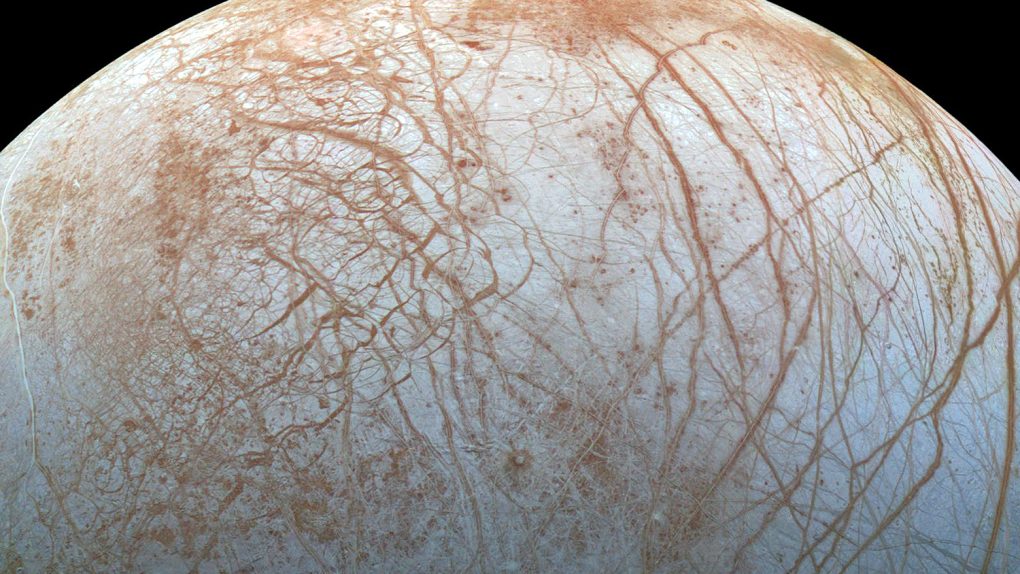

Jupiter’s moon Europa has offered tantalizing hints at its life-support potential for decades. Scientists have long known that the moon is covered in thick ice, but evidence that liquid water still flows deep inside has remained sparse. Now, a research team using satellite imagery of Europa has confirmed the presence of water vapor around the frosty world.

The research, which is the subject of a new paper published in Nature Astronomy, is exciting for a number of reasons, but there’s no denying that the ongoing search for extraterrestrial life is on everyone’s mind.

“Essential chemical elements (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur) and sources of energy, two of three requirements for life, are found all over the solar system. But the third — liquid water — is somewhat hard to find beyond Earth,” NASA’s Lucas Paganini, who led the study, explains. “While scientists have not yet detected liquid water directly, we’ve found the next best thing: water in vapor form.”

Europa shares many of its features with another moon in our solar system, Saturn’s Enceladus. The Cassini probe which traveled to Saturn and spent over a decade studying the planet and its moons revealed Enceladus to be an icy ball with a crust that hides an ocean of liquid water. Massive cracks in the ice spew water into space, where it instantly freezes.

Astronomers have believed that the same may be true of Europa. The fact that water vapor has now been detected around the moon points to eruptions of liquid water through the ice. That water has to come from somewhere, so it would seem likely that Europa has an ocean of its own, and that could mean life.

Finding that life, however, is easier said than done. It would require a mission to the moon itself, either landing on the surface or, at the very least, getting close enough to sample a plume of water being shot into space. Proposals for the upcoming Europa Clipper mission, set to launch in 2025, have included sending a secondary orbiter to search for biosignatures. If that additional hardware is sent along, it could return data that confirms the presence of life in some form beneath the ice.