Scientists Spot Rare 'Boomerang Earthquake' In The Ocean

- Scientists have recorded the first evidence of a so-called "boomerang earthquake" occurring deep in the Atlantic Ocean.

- A boomerang occurs when a fracture proceeds in one direction before rapidly changing course and traveling back in the opposite direction at even higher speeds.

- The researchers hope that these observations can help better prepare early warning systems and models that predict earthquake damage.

Earthquakes are relatively well-understood as a natural phenomenon. They occur when pressures build up between two pieces of Earth's crust and then eventually release, causing intense shaking that can cause serious damage if it happens near a populated area. They rank in intensity from incredibly mild to absolutely disastrous, but a new study reveals some tantalizing details about one of the rarer types of earthquakes.

Scientists call it a boomerang earthquake, and its name tells you a lot about how it works. The quake begins along a fault line between two pieces of Earth's surface, traveling in one direction along the fault before abruptly reversing direction. This almost never happens, but when it does, the fracture's return journey happens at incredible speeds, and researchers recently recorded one as it happened.

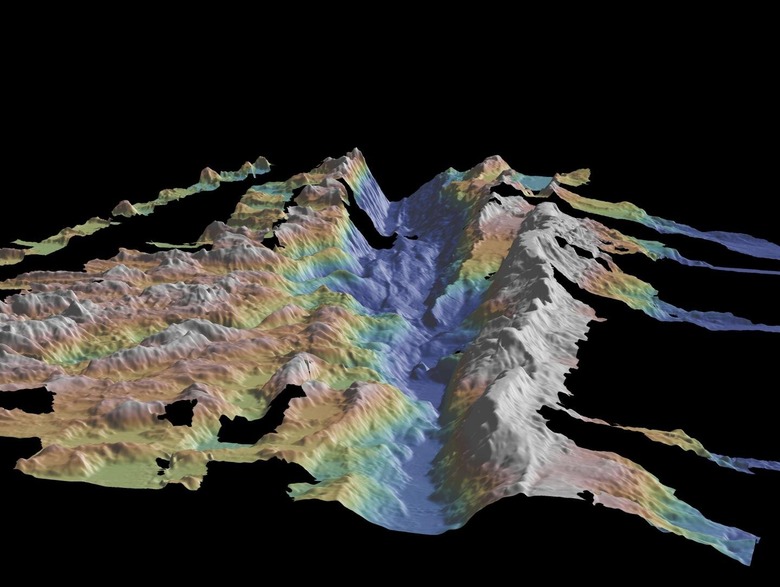

As researchers report in a new study published in Nature Geoscience, a magnitude 7.1 earthquake in the Atlantic Ocean back in 2016 appears to have been one of these rare types of earthquakes. The earthquake was detected using underwater seismic sensors, and it appeared to first move in one direction before rapidly switching back and fracturing even more in the opposite direction at an incredibly fast speed.

"Whilst scientists have found that such a reversing rupture mechanism is possible from theoretical models, our new study provides some of the clearest evidence for this enigmatic mechanism occurring in a real fault," Dr. Stephen Hicks, first author of the study, said in a statement. "Even though the fault structure seems simple, the way the earthquake grew was not, and this was completely opposite to how we expected the earthquake to look before we started to analyze the data."

The researchers believe this phenomenon is quite rare, but because of that it also hasn't been widely studied. The fact that this kind of thing can happen isn't factored into models that predict earthquakes and certainly haven't been accounted for in early warning systems and other networks of information designed to keep people safe.

The "back-propagation" of the rupture is believed to be linked to deep splits that reach weak areas of the fault and then snap back the opposite direction.

"We suggest that deep rupture into weak fault segments facilitated greater seismic slip on shallow locked zones," the researchers write. "This highlights that even earthquakes along a single distinct fault zone can be highly dynamic. Observations of back-propagating ruptures are sparse, and the possibility of reverse propagation is largely absent in rupture simulations and unaccounted for in hazard assessments."