The little we already know about exoplanets — that is, planets we’ve spotted or detected outside of our own Solar System — paints many of them in a very strange light. They’re often incredibly hot or frigidly cold, and as for their weather, well let’s just say you wouldn’t last more than a couple of second on the majority of them. Kepler-13Ab is one such planet, with a dayside temperature that approaches 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Oh, and sunscreen falls from the sky like snow. Yeah, it’s a real weirdo.

Astronomers from Penn State recently used the impressive capabilities of the Hubble Space Telescope to investigate the exoplanet and learn a bit more about how it works. Their results paint a picture that is almost hard to even imagine, but science says it’s legit. The study was published in The Astronomical Journal.

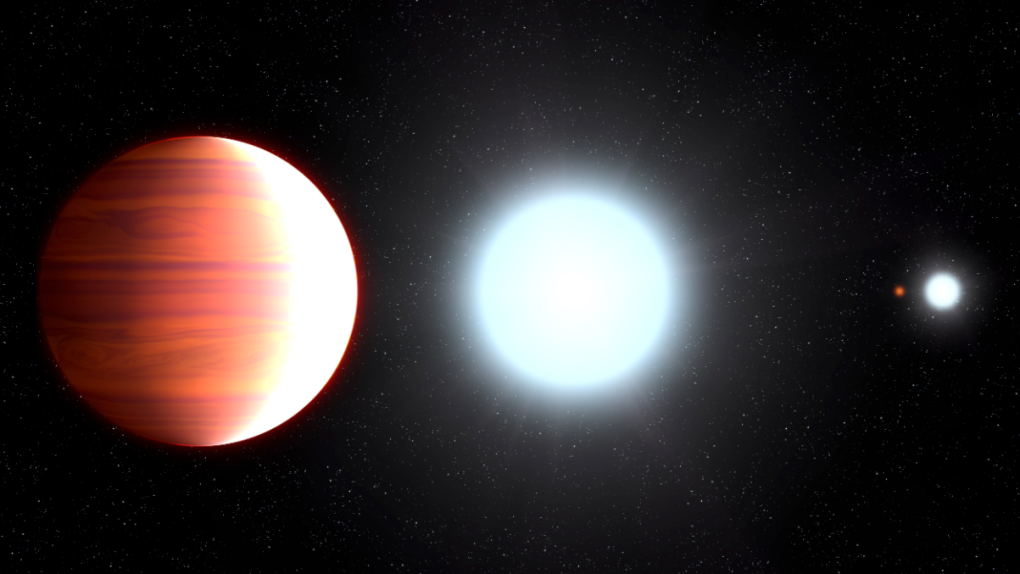

For starters, Kepler-13Ab is a massive gas giant that makes even the mighty Jupiter look like a small fry. The planet is also extremely close to its host star, and that has caused it to become tidally locked — that is, the planet has a day side and a night side which never change, as the planet orbits its star with the same side always facing towards its sun.

During their atmospheric study of the planet, the research team discovered that titanium oxide — the active ingredient in sunblock — on the planet’s hot side gets superheated and, as with all hot gas, rises. When it reaches a high enough altitude, the gas begins to cool as its surrounding atmosphere is cooler than it is near the planet, causing the titanium oxide to crystalize into clouds. Then, because the planet’s gravitational pull is so great, that crystalline material tumbles down like snow on the nighttime side of the planet.

“Presumably, this precipitation process is happening on most of the observed hot Jupiters, but those gas giants all have lower surface gravities than Kepler-13Ab,” Thomas Beatty, assistant research professor of astronomy at Penn State, explained. “The titanium oxide snow doesn’t fall far enough in those atmospheres, and then it gets swept back to the hotter dayside, revaporizes, and returns to a gaseous state.”