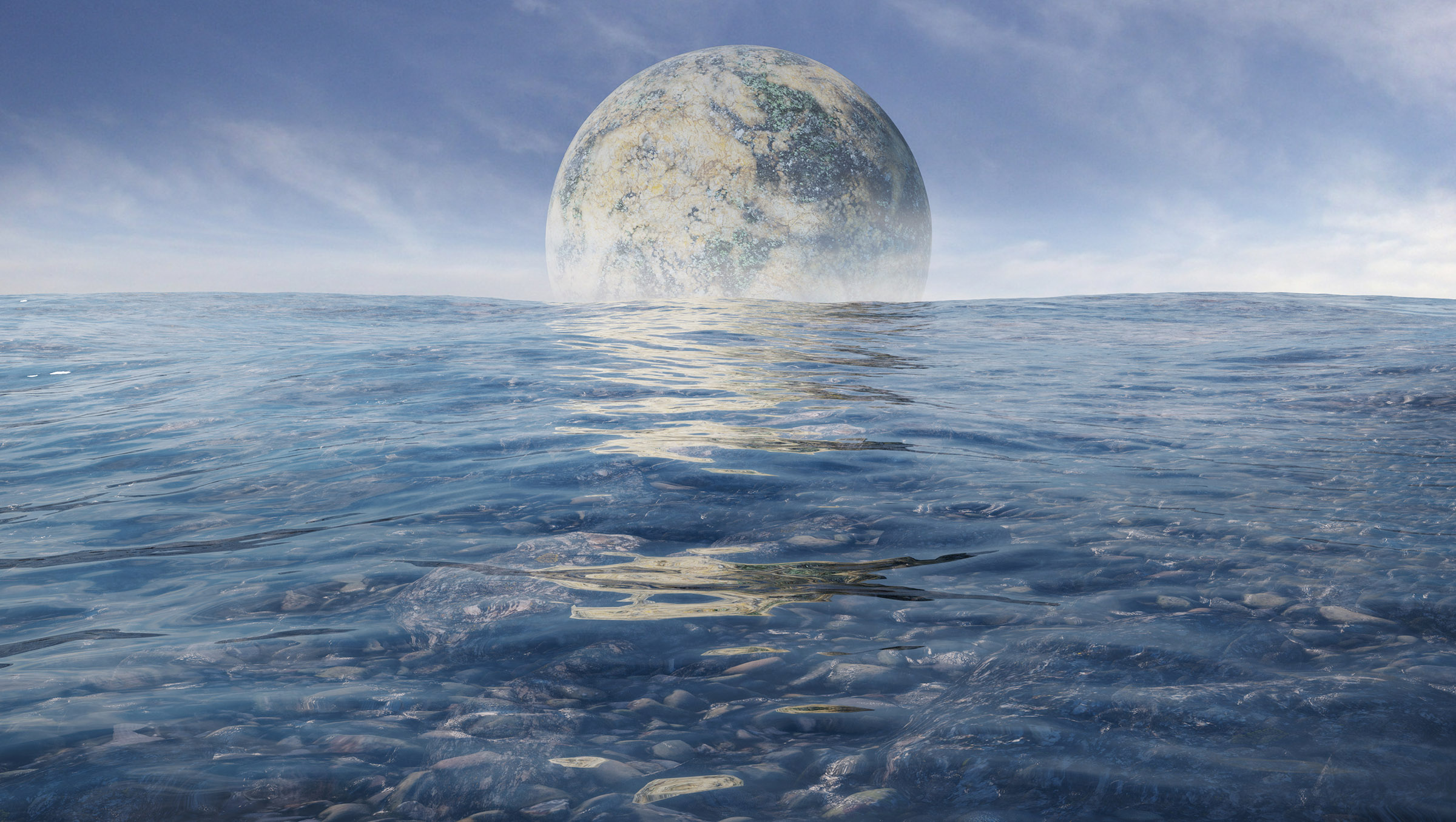

Two planets that astronomers discovered on the Kepler mission may not be the rocky, Earth-like bodies that we originally believed. Instead, a new study suggests that they could be two water worlds, and that they are less dense than astronomers originally posited.

What’s intriguing about these worlds is that they are believed to be somewhat similar to Europa, which is a rocky core encased in water and capped in ice. However, these two worlds are closer to their star than Europa and its planet are. As such, scientists believe that the surface of the planets most likely blurs between liquid water and vapor.

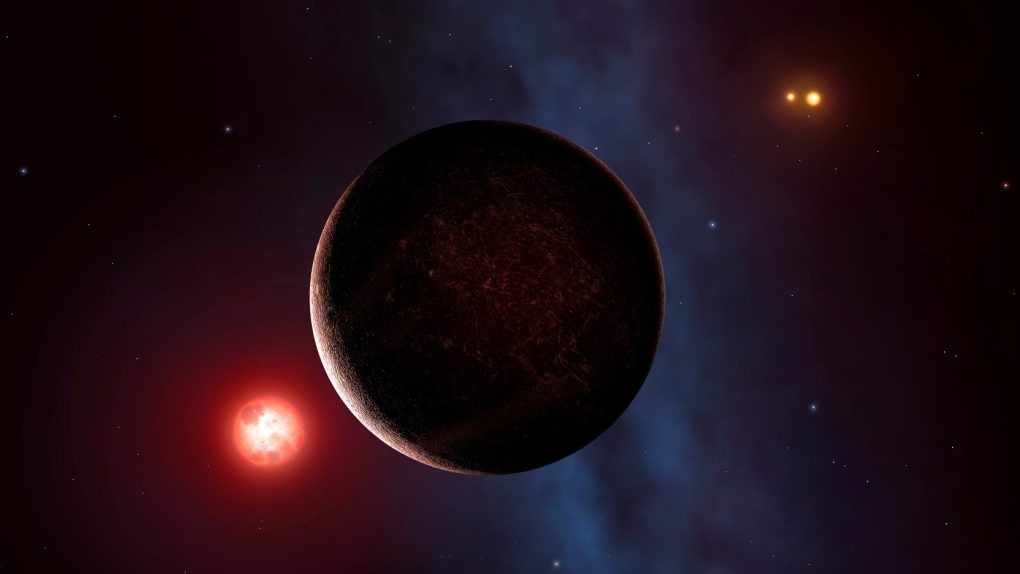

When we first discovered these water worlds in the Kepler system, there wasn’t anything especially intriguing about them that warranted a second look. However, astronomers believed that it would be a good candidate for research on the atmospheres of the exoplanets within the system. As such, new studies on the planets we discovered there began.

To dig deeper, the researchers began to look at data of the system captured by the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes. Because the planets are so close, they create what astronomers call “transit timing variations,” which means that the planet doesn’t show up in front of its host start exactly when the orbit would normally take it there.

This means that any data gathered by looking at the transit of the planets in a system will be out of sync in a way. However, by looking at data gathered using the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes after the discovery of the water worlds, the researchers were able to create a timeline based on a seven-year span. This provided more details about the worlds found in Kepler.

The researchers then found that the data they gathered from the Kepler mission didn’t allow for correct transiting timetables. Instead, they had to change the equation slightly to that of a four-planet model instead of the three-planet model they were using before. When done, they discovered that the transit times then made more sense.

It was this change in the model that forced the astronomers to reevaluate how they viewed the two worlds they believed to be rocky and dense. With a four-planet model, it made more sense for the planets to be less dense, perhaps even water worlds. That’s because the planets are all so close together, which means the gravitational pull from each one affects the others.

But, this fourth world has yet to be seen transiting in front of the star within the Kepler system. As such, the water worlds are not the only mystery that keeps astronomers looking to this star system. When we do discover it, if we’re able to learn more about it, perhaps it could provide even more proof of these water worlds. Or, it could turn everything we know on its head.