- The National Institutes of Health produced new imagery of the novel coronavirus that causes the deadly COVID-19 disease.

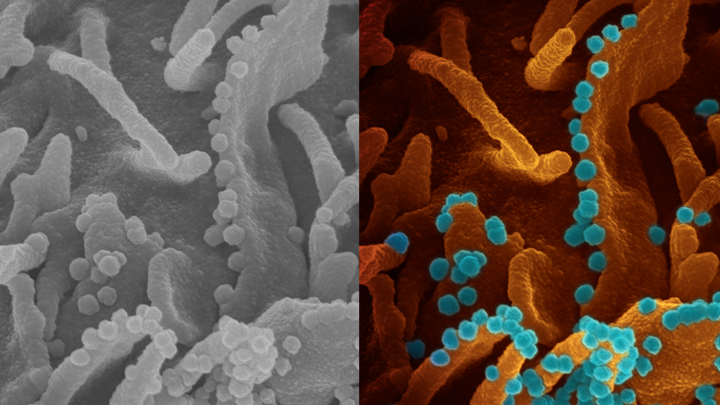

- The image shows SARS-CoV-2 replicas exiting the body of a dying cell that had been infiltrated by the virus.

- The created was obtained with the help of a sophisticated microscope and it shows us how the novel coronavirus kills cells.

- Visit BGR’s homepage for more stories.

Imagine there’s anywhere from a few thousand to a few million thugs waiting on your doorstep to attack you every time you leave the house. That’s how you have to think about the invisible coronavirus threat. COVID-19 is a very serious disease and it’s out there, even if you can’t see the tiny novel coronavirus that causes it. Even people who appear to be healthy could have it and they could pass it on to you with ease. The virus is quite good at spreading in a community, and it’s very devious. Symptoms might not appear up to 14 days after the infection, and that’s if they appear at all. That’s why some sort of social distancing might be required for quite a long time to come, even after authorities relax some of the current rules.

If you still don’t believe the SARS-CoV-2 is a real danger or if you just want to see this horrific microorganism that upended your life, we have just the image for you. The following picture shows exactly how the virus kills the cells it infects.

Coronaviruses are 125 nanometers wide, which means you can fit some 800 of them in the width of a human hair. You won’t see the virus out in the wild, hence my thug analogy. But it’s there, and all it takes is for one of this tiny thing to get into your respiratory tract to initiate a chain reaction that can result in death, in a worst-case scenario.

What the virus does is to hook up to specific cell receptors, and then it binds to that cell. That’s where the virus takes over the cell’s chemical plan to replicate itself. All the copies the cell produces pour outside of it, killing it in the process, and all those virus cells go on to attach to other cells. It all happens over and over until the immune system can put a stop to it.

The lung is SARS-CoV-2’s preferred location, and an attack on the lungs is what can lead to complications. A study from 1982 concluded that alveolar type I cells are one of the largest cells in the lung, having a mean volume of 1,764 micrometers — that’s 1.764 million nanomaters. So a lung cell has plenty of space to accommodate the novel coronavirus and allow it to replicate.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) was able to take a photo of the processor of coronavirus shedding (see above). Viral shedding is something you’ve heard on the news lately and refers to the process of the virus existing the dying cell after having replicated itself inside it. It was the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which used advanced technology to capture the COVID-19 virus leaving a dying cell.

The researchers used a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to capture the particles. The entire process is quite sophisticated as it doesn’t rely on light to capture the photo:

SEM enables visualization of particles, including viruses, that are too small to be seen with traditional light microscopy. It does so by focusing electrons, instead of light, into a beam that scans the surface of a sample that’s first been dehydrated, chemically preserved, and then coated with a thin layer of metal. As electrons bounce off the sample’s surface, microscopists such as Fischer are able to capture its precise topology. The result is a gray-scale micrograph like the one you see above on the left. To make the image easier to interpret, [Elizabeth] Fischer hands the originals off to [Rocky Mountain Laboratories] RML’s Visual Medical Arts Department, which uses colorization to make key features pop like they do in the image on the right.

Fisher, who took the photo, is the head of RML’s Electron Microscopy Unit. As you might have guessed, the tiny blue spheres are SARS-CoV-2 replicas that exit the orange-brown dying cell. The cell is an epithelial cell from the kidney of a monkey. The same sort of viral shedding occurs in the human body as well.