- Severe COVID-19 cases often require intubation and a mechanical ventilator for the patient to breathe, and he or she could be on a machine for weeks before being able to breathe unassisted again.

- Medical professionals dealing with the novel coronavirus outbreak in the US are looking at frameworks to decide which patients can get access to this life-saving therapy in overcrowded hospitals.

- Ventilators are in short supply in hot zones like New York, where doctors will have to decide who has a chance to live and die of COVID-19.

- Visit BGR’s homepage for more stories.

The sad reality is that many countries have failed to prepare accordingly for the novel coronavirus pandemic. The outbreak in China needed weeks to become a worldwide emergency and reached a pandemic status in just a couple of months. But many governments failed to take the basic measures that could have helped mitigate the disaster. Tests and personal protective equipment have been in short supply in most regions, and the situation might get worse before it gets any better. Ventilators — the machines that can push oxygen into the failing lungs of severe COVID-19 victims — are scarce in hot zones, and companies around the world can’t just manufacture and ship them overnight. Access to a ventilator might mean the difference between life or death for many people. But as hospitals become overcrowded with COVID-19 patients, healthcare professionals might be forced to make tough choices. They’ll decide who will get access to a ventilator, and therefore, who lives and dies.

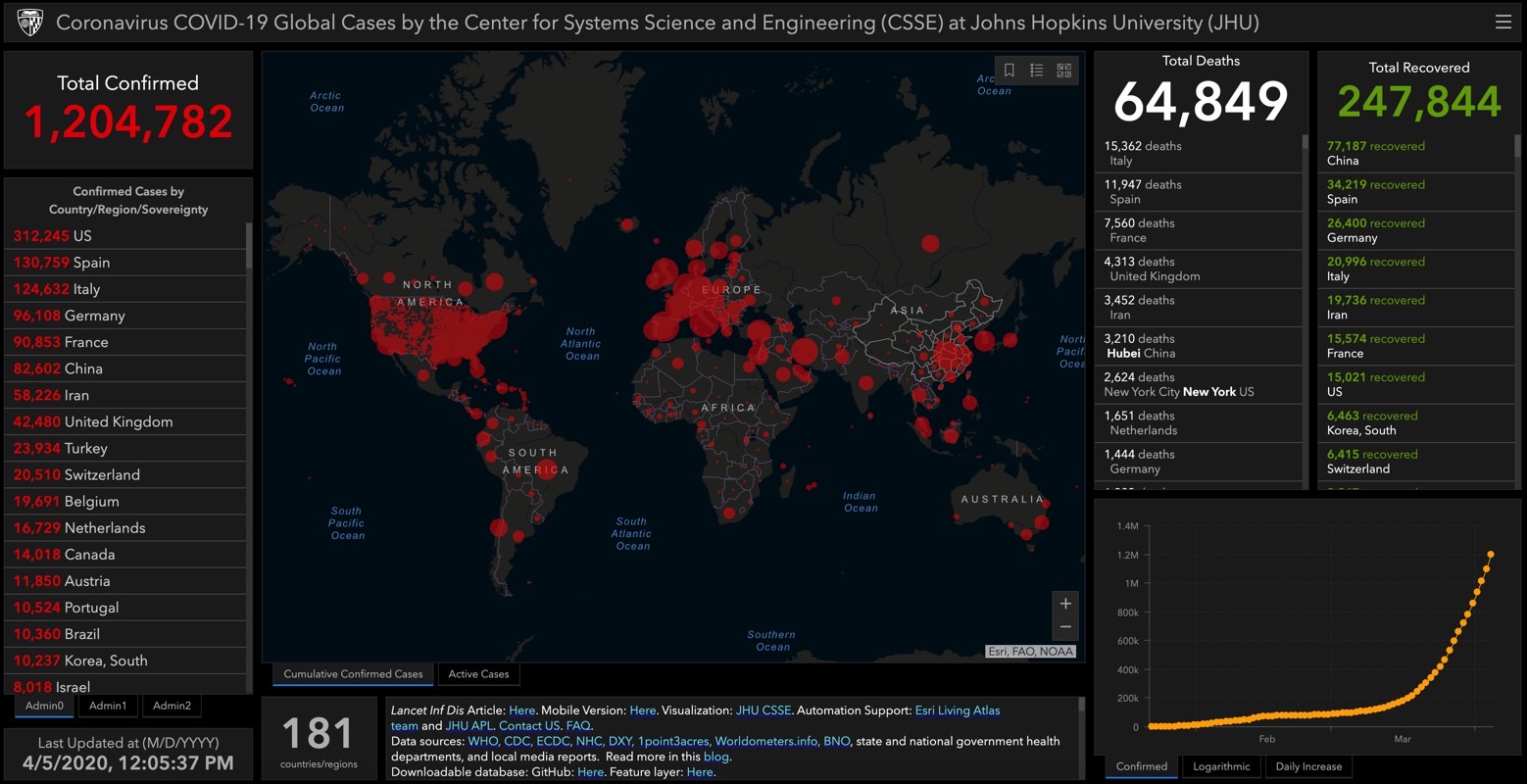

As of Sunday morning there were over 1.2 million COVID-19 cases in the world, including nearly 65,000 casualties. The US had more than 312,000 cases and over 8,500 fatalities. More than a third of cases and nearly half of fatalities are in New York alone.

“Physicians who work in parts of the world that don’t have adequate resources have had to make decisions like this maybe even on a routine basis, but physicians in the United States have never faced anything like this before,” director of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School Dr. Robert Truog told CNN. “It is going to be extremely difficult.”

Truog worked with hospitals to develop policies that determine who can receive intensive care during the crisis. One of the best frameworks comes from University of Pittsburgh and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UMPC) professor Dr. Douglas White.

White, a professor of critical care medicine, elaborated his guidelines more than a decade ago during the avian influenza epidemic. It’s a point system meant to determine a patient’s likelihood of benefiting from ICU care that takes two things into account: Saving the most lives and greatest number of years.

The lower the patient scores, the higher their prioritization for care. In the system’s eight-point scale, the first four points illustrate the patient’s likelihood to survive hospitalization, and the last four points assess whether, assuming they survive hospitalization, they have medical conditions associated with a life expectancy of less than one year or less than five years.

White’s framework directs doctors to prioritize life cycle in case of a tie, and treat younger patients. But White explained that everyone is eligible for treatment, no matter of age or health conditions

“Everyone who is normally eligible for intensive care remains eligible in a public health emergency,” White said. “It is critical to make clear that stereotypical judgments about quality of life have no role in these decisions, and no one is disqualified from treatment because of disabilities.”

Triage policies may differ from state to state, but they’ll have to be adjusted for the COVID-19 pandemic. White told CNN he believes that triage committees should be composed of non-frontline doctors to “enhance objectivity, avoid conflicts of commitments, and minimize moral distress.”

There may be various medical conditions that require ICU care as well as ventilator access. But COVID-19 patients may have to stay on a machine for a few weeks instead of just days, as is the case for other conditions, and that’s why the ventilators are running out. What’s worse is that even access to a ventilator doesn’t guarantee recovery. Some people will still die and others might experience complications down the road.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo said during Thursday’s briefing that the state only had “about six days left” of ventilators in the stockpile at the current rate of hospitalization and intubation. “If a person comes in and needs a ventilator and you don’t have a ventilator, the person dies. That’s the blunt equation here,” Cuomo said.

While doctors in some regions like New York might have to make difficult decisions when ventilators start running out, not all hospitals will have to triage patients right away. The main takeaway for everyone else is that social distancing is essential for helping yourself and hospitals. The longer we stay indoors, the less likely it is to catch the new virus and risk developing a severe COVID-19 case. And that’s the only way to avoid hospitals from being overwhelmed by patients, and prevent doctors from having to choose who lives and who dies.