Netflix's New Wes Anderson Movie Already Has A Perfect 100% Score On Rotten Tomatoes

The debut of a new Wes Anderson film almost always feels like a cause for universal celebration. He's a darling of critics, who remain forever and always enamored of his visual aesthetic and Brechtian flair. To audiences, his films like The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar – coming to Netflix later this month — are like a steaming mug of warm cocoa; a simple pleasure it's near-impossible to dislike. In both style and substance, the madcap director's movies are conspicuously grand, inventive, reassuring, and sometimes even profound, though his upcoming Netflix movie also finds him trying something a little different.

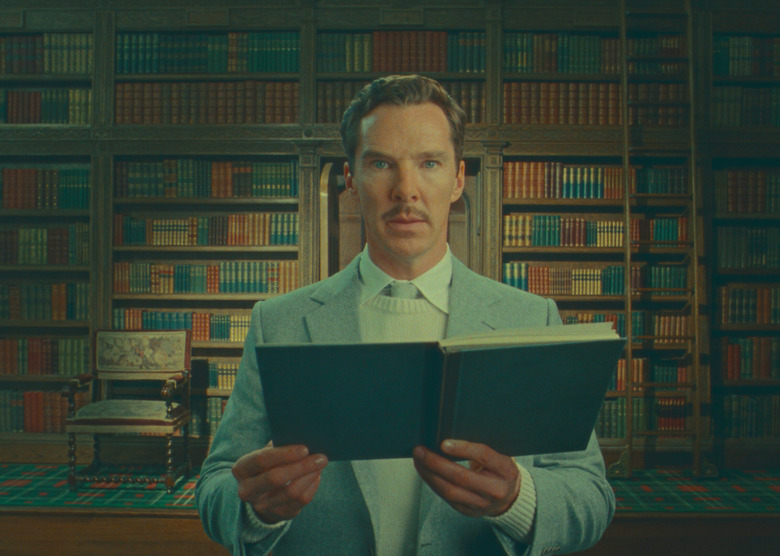

To be sure, all of the familiar Wes Anderson hallmarks are here in this Roald Dahl adaptation. The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar is about a rich man who learns about a guru who can see without using his eyes — and who then sets out to master the skill in order to cheat at gambling. It's so "wonderful," in fact, that the movie (starring Benedict Cumberbatch, Ralph Fiennes, and Ben Kingsley) already has a perfect 100% critics' score on Rotten Tomatoes.

With a tight running time of just 40 minutes, however, this Netflix movie feels more like episodic Anderson — and is actually one of four short Dahl adaptations in total from the director that will hit Netflix this month (the others are The Swan, The Ratcatcher, and Poison). "I had the thought to try to adapt Henry Sugar maybe almost twenty years ago, when I was staying at Gipsy House (which is Dahl's family house in Buckinghamshire)," Anderson says in a Netflix promotional interview. "And I had a simultaneous thought which was: 'I don't know how to do this.'

"But over the years, the Dahl family — Felicity Dahl and Dahl's grandson Luke Kelly — kept the rights to the story set aside for me. When I finally had the moment of inspiration, the idea was: 'I am equally interested in the way Dahl tells the story as I am in the story itself.'"

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, which comes to the streamer on Sept. 27, is a Dahl story that I daresay the average viewer will be less familiar with, if at all, relative to Dahl's more celebrated works like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. But don't worry; it's not long before Anderson's grab bag of moviemaking tricks — from having Fiennes on hand as Dahl himself reciting the short story, to letting the action unfold in an old-fashioned movie studio — will take the director's fans once again to that old familiar place. The catalyst, this time, being a sweet, happy tale from one of the greatest storytellers of the 20th century.