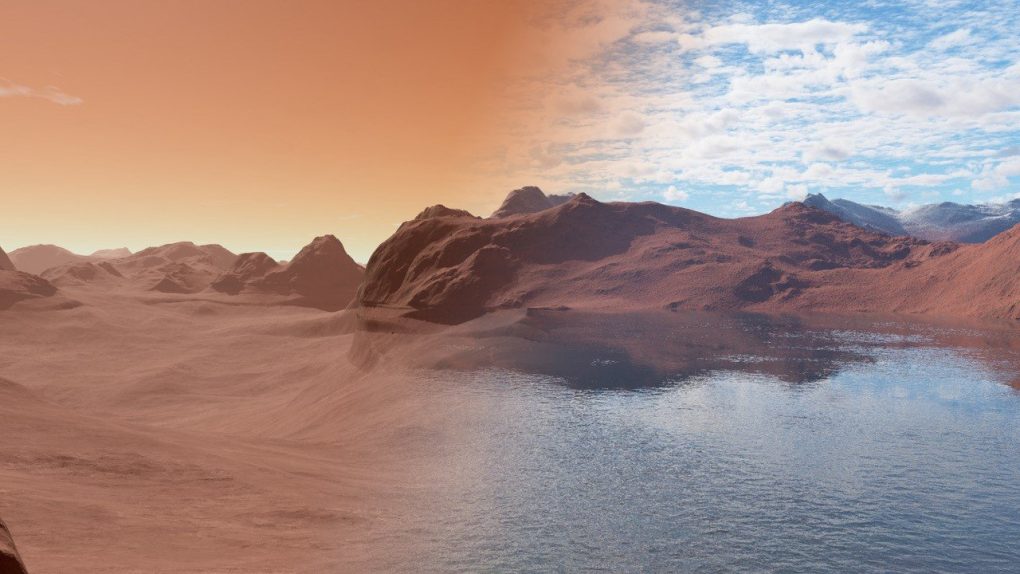

Scientists have a serious love affair with Mars. If (hopefully “when”) mankind sets foot on another planet, Mars is almost certainly going to be the one, and it’s so much like Earth in terms of composition that there’s still a chance that we might find evidence of extraterrestrial life there. No, I’m not talking about a race of Martian “Warrior Women,” but fossils that reveal microbs or other primitive life forms that may have once inhabited the lakes and rivers we believe covered the planet millions of years ago.

We already have rovers taking samples of Martian soil and studying the makeup of the Martian landscape, but we haven’t found anything to suggest the presence (either current or in the past) of life. Monica Grady, Professor of Planetary and Space Sciences at The Open University, says that if we really want to see whether or not Mars once supported some form of life, we’re going to need to be able to study Mars samples here on Earth.

Effectively studying Martian rock samples requires some pretty sophisticated hardware. The newest Mars rovers and landers from NASA and the European Space Agency are incredibly high-tech, but they simply aren’t capable of performing the kind of analysis that is needed to provide evidence of life. For that, we need to bring rocks back to Earth, and we have to do so in a way that doesn’t risk contaminating either planet.

“The technology that would help us to avoid contaminating Mars with Earth microbes and vice versa (if there turns out to be life there) – “breaking the chain of contact”, where a capsule launched from Mars’ surface with a sample could not return to Earth, as it would risk contaminating our biosphere – is also well developed now,” Grady says. But how exactly do we make it all happen?

NASA’s Mars 2020 rover and the ExoMars rover built by ESA are both capable of preparing samples for return to Earth, but that’s only the first step in a very complicated process. The two agencies are already working out the details, but it’s hardly a walk in the park. Completing the handoff would require a Mars Ascent Vehicle to take off from the Red Planet and successfully enter orbit. Meanwhile, a separate vehicle would have to meet up with the orbiter and take possession of the samples before venturing back towards Earth. None of his has ever even been attempted before.

Complicating matters further is the current budget woes of NASA. The agency doesn’t have a lot of money to play around with these days, and even by leaning on commercial launch companies to help cut costs, organizing multiple launches for the purpose of returning Mars samples to Earth will be incredibly expensive. Thankfully, NASA and ESA have pledged to tackle the challenge together, so hopefully the pursuit of science won’t be held up by an empty wallet.