that T-Mobile and Sprint have agreed a deal to merge in principle, with an announcement set to come in October. A merged company (T-Sprint? S-Mobile? Oath?) would be a formidable player in terms of subscribers, with about as many customers as Verizon or AT&T. But there’s a much bigger question for existing customers: What would the network look like?

Both Sprint and T-Mobile have a similar network presence: good in cities and urban areas, not as good as Verizon or AT&T in rural areas. Combining Sprint and T-Mobile’s networks wouldn’t instantly bring the network up to par with Verizon or AT&T, but it would create a brand-new and very dangerous player.

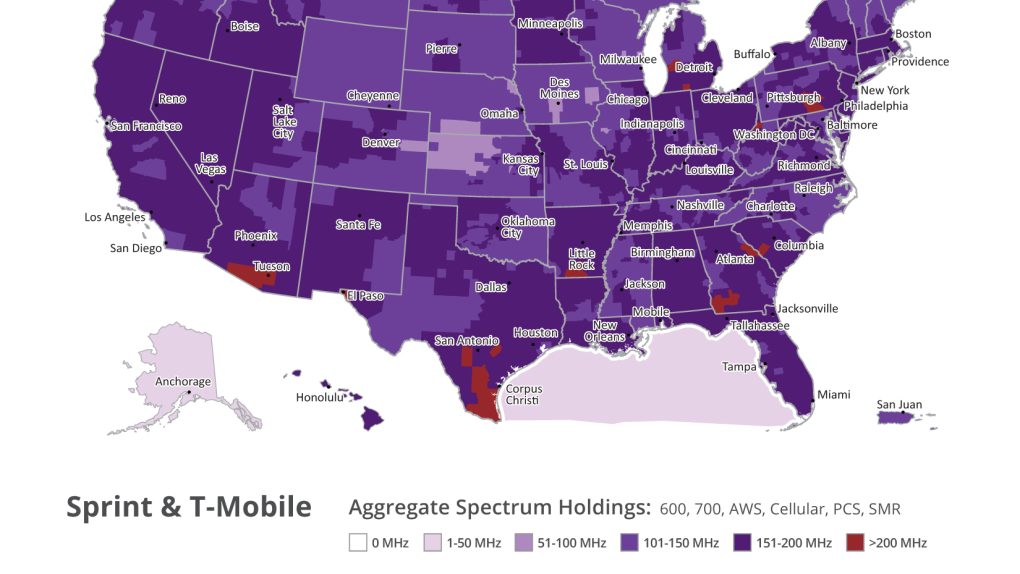

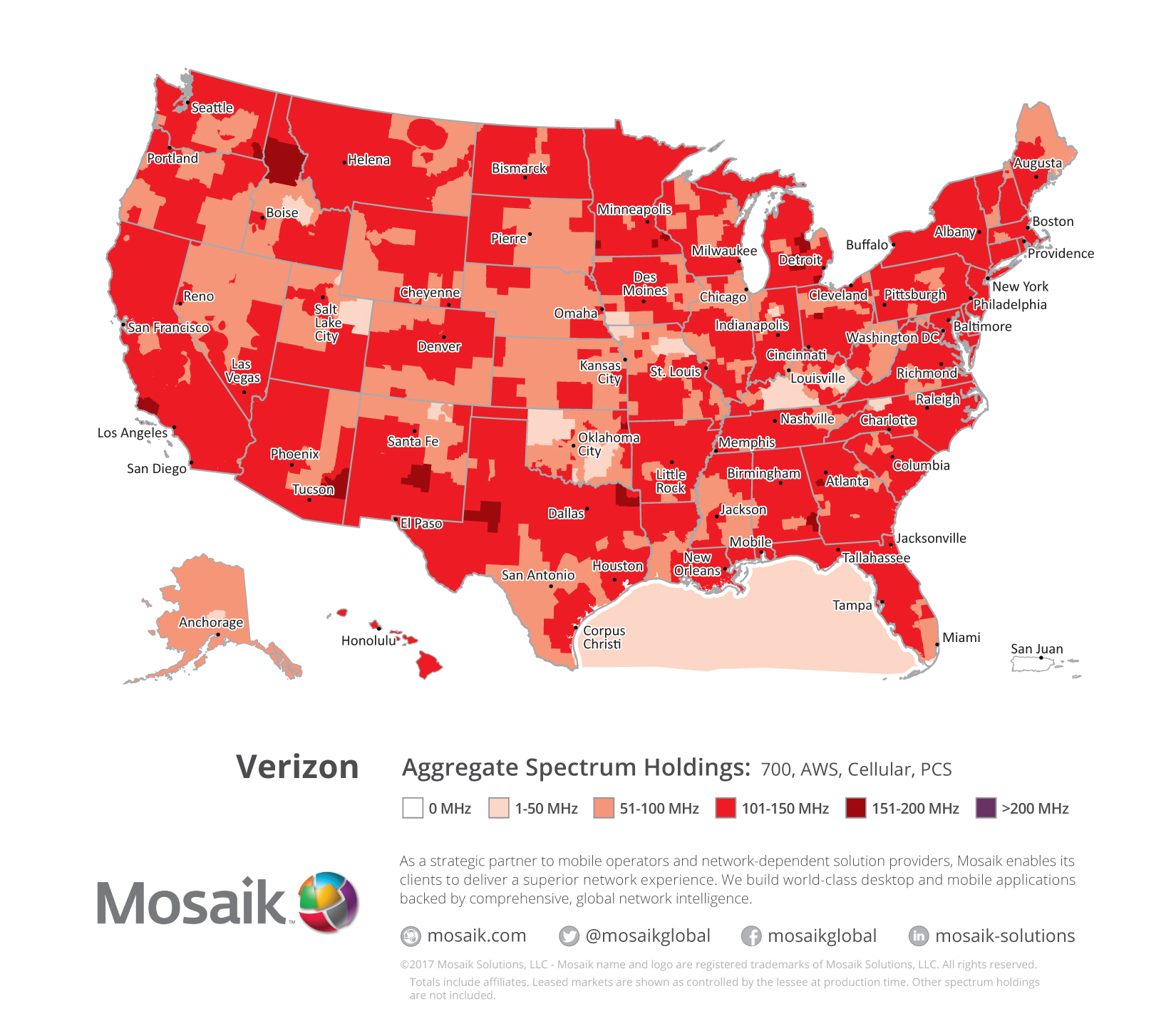

Spectrum licenses are the ultimate deciders of how good a network can be. You can throw all the towers and micro-cells at a wireless network that you want, but without enough wireless spectrum to build out, a network will never be good. Verizon’s long-term holdings in low-band spectrum have historically given the company an edge, especially combined with enough money to invest in infrastructure.

Sprint and T-Mobile, on the other hand, have long been limited. Sprint has buckets of high-band spectrum, which is great for short-range communications, but bad for getting enough coverage to make a voice call in rural areas. T-Mobile historically lacked low-band as well, but thanks to its $8 billion investment in 600MHz spectrum this year, its coverage should be getting much better in the near future.

So what would combining those two networks do? John Gilmer, VP of Data Integrity at network intelligence firm Mosaik, said that “a combined network would be very competitive in the future, thanks to nice spectrum holdings.” He said he’d be “very surprised” if Sprint doesn’t have to sell some of its high-band spectrum as a regulatory condition of any merger, but nonetheless, Sprint-T-Mobile would be in good shape spectrum-wise. You can compare the spectrum map of a combined Sprint-T-Mobile at the top of this article with one of Verizon to understand how the two networks would measure up in the long run.

Consumers shouldn’t expect to see many immediate benefits, though. Combining two separate wireless networks is a long and torturous process, especially because T-Mobile and Sprint use different LTE bands, and different 2G networks. (T-Mobile uses GSM and Sprint CDMA.) Gilmer thinks it’s a ballpark of months and years, rather than weeks, until T-Mobile customers will be able to use Sprint’s network and vice-versa.

For the two companies, the benefits of any merger are going to be cost savings and increased revenues to spend on investment, rather than suddenly having a better network.

But for consumers, those cost savings might end up hurting. The wireless industry is currently competitive, thanks to the variety in big wireless players. Verizon and AT&T have the best network, the most subscribers, and the highest prices. Sprint and T-Mobile have to compete on features (like unlimited data) or price. That competition helps keep prices down across the board, and forces AT&T and Verizon to offer unlimited plans — even if it’s bad for the bottom line and the network.

With Sprint and T-Mobile merging, that’s all likely to go away. We can see what happens when you have three equally-sized wireless players by looking at Canada. Competition is low, unlimited plans are nonexistent, and a reasonable plan costs over $100 a month.

Normally, such a mammoth merger would be subject to close scrutiny from the FCC, but the new-look FCC under Trump appointee (and former Verizon lawyer) Ajit Pai has shown no signs of wanting to be tough on big business. It’s moved to strike down net neutrality rules, showed no interest in limiting the massive AT&T-Time Warner merger, and is generally viewed as being unlikely to stop a Sprint-T-Mobile merger.