We owe a lot to our Sun, and without it, well, we wouldn’t be here at all. Scientists have studied our star for a long time, and learned plenty about it over the years, but one of the mysteries that has endured for centuries is the sunspot cycle.

Every 11 years, the Sun produces far more sunspots — dark blotches on the star’s surface — than at any other time, and this cycle has always left researchers scratching their heads. Now, a new study out of the University of Washington suggests a possible explanation, and it hinges on the behavior of plasma.

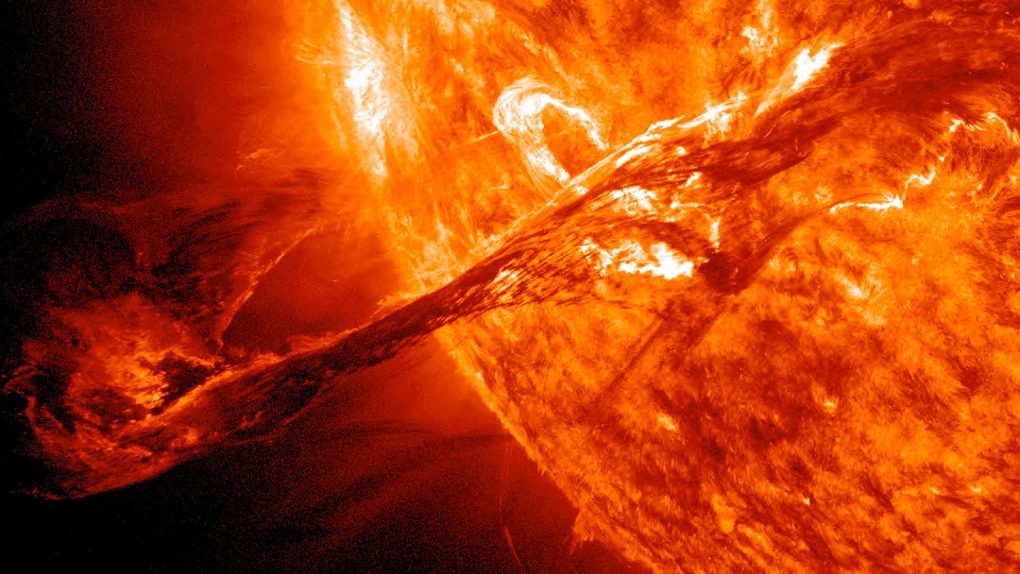

The research is based around a model of the Sun that the scientists came up with after extensive study. In the model, the star is covered in a thin, flowing layer of plasma that moves at varying rates, swirling and twisting around, generating magnetism.

“Every 11 years, the sun grows this layer until it’s too big to be stable, and then it sloughs off,” Thomas Jarboe, a professor at the university and lead author of the study published in Physics of Plasmas, said in a statement.

It had been thought, Jarboe says, that sunspots came from deep within the Sun itself, with forces blasting plasma off of the surface and leaving behind a kind of stellar scar in its place. This study suggests that sunspots are actually born right where we see them, in a very thin layer of plasma just below the solar surface.

The model used by the scientists was born out of previous research into fusion reactors, which offered hints as to how plasma on the Sun may twist and accumulate until it is violently shed, leaving a sunspot in its wake.