Scientists at UCLA have uncovered a new source of super-fast electrons that rain down on the Earth. When interacting with the Earth’s atmosphere, these electrons create beautiful phenomena like the Northern Lights. However, scientists say they also pose a significant threat to spacecraft, satellites, and astronauts. The scientists combined data captured by UCLA’s ELFIN satellites and NASA’s THEMIS spacecraft to study the new “electron rain”.

Discovering the source of the ‘electron rain’

The researchers say they observed the unexpected electron precipitation from a low-Earth orbit using UCLA’s ELFIN satellites. These satellites are part of the ELFIN mission and include two satellites the size of bread loaves. They published their findings in the journal Nature Communications this month.

After discovering the electron rain, they also looked at data from NASA’s THEMIS spacecraft. This allowed them to get a broader look at the effects of the raining electrons using distant observations. By doing this, the team was able to determine that Whistler Waves are behind the electron precipitation.

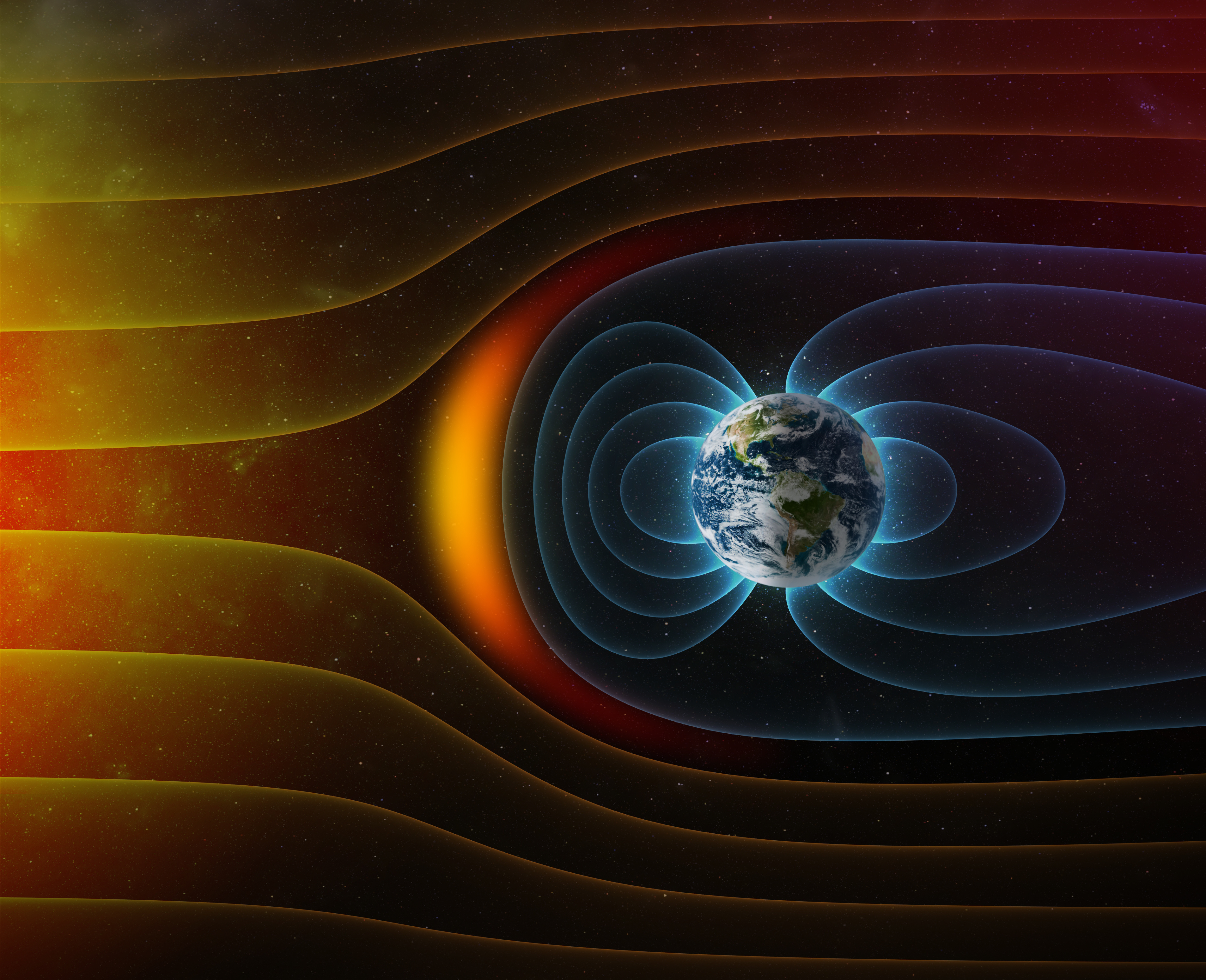

See, electrons typically travel between the Earth’s north and south poles within what we call the Van Allen radiation belts. These belts are a key part of the events that take place within the near-Earth space environment. However, when Whistler Waves are generated within the radiation belts, the electrons grow more energized and speed up.

When they start to move faster and gain more energy, the electrons are more likely to fall through the belts and into the atmosphere, creating electron rain.

Why scientists are worried about Whistler Waves

So, a few extra electrons make it into the atmosphere and possibly make more aurora borealis. That isn’t that big of a deal, right? Well, the researchers say it could prove hazardous to satellites, spacecraft, and even astronauts.

That’s because whenever solar flares cause geomagnetic storms that affect our near-Earth space, they also affect the Earth’s magnetic environment. In the past, we’ve seen reports of solar storms causing lost sea mines to explode due to the intensity of the energy that hit the Earth at the time.

When these storms happen, electron rain is even more likely as electrons fall from the radiation belts that surround our planet. Current models and theories for space weather don’t typically account for this kind of electron precipitation. This is why it’s so important for us to study it now.

Scientists say that Whistler Waves can have a massive effect on the Earth’s atmospheric chemistry. And, if that was to happen while a spacecraft or satellite was passing through a low-Earth area, then it could pose risks we haven’t previously accounted for.

The discovery of this electron rain is also a huge indicator of just how connected space and the Earth’s upper atmosphere is. It’s also a great reminder of just how important understanding those elements can be to providing safe travel for astronauts and spacecraft passing through the atmosphere in the future.