Researchers Say 50 Percent Of Black Holes Burp Up Star Remains Years Later

A new study claims that approximately 50 percent of all black holes that consume stars will burp up star remnants years later. Astronomers say they made the discovery after observing several black holes engaged in tidal disruption events (TDEs) for multiple years.

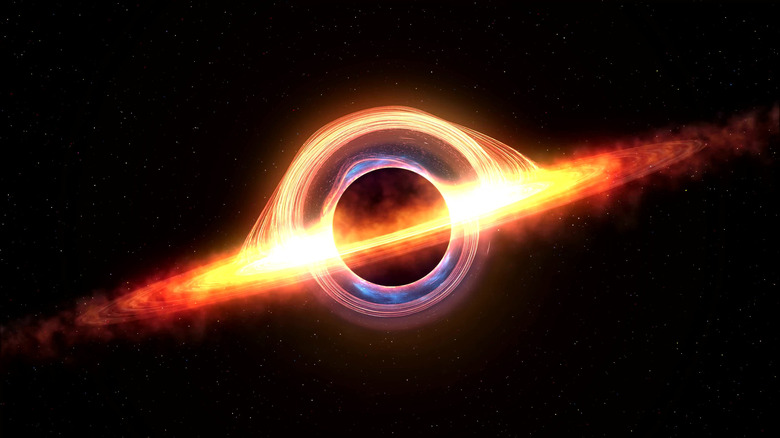

TDEs typically manifest whenever a star comes too close to a black hole. The gravitational pull of the black hole results in the exertion of extreme tidal forces on stars, essentially ripping them to shreds. Any stars that are unlucky enough to fall into a black hole experience a rapid process of disintegration. This event is accompanied by a significant release of electromagnetic radiation in the visible light spectrum.

This leftover material coalesces into a thin, disk-shaped structure, which scientists call an accretion disk, while a portion of the rest of the shattered star is blasted away from the black hole. In turn, this disk makes the gradual transport of matter to the black hole easier. The accretion disk experiences instability early in its inception, which causes material inside the disk to move and collide.

Scientists used radio waves to observe the jets that are produced as a result of these collisions. Usually, however, astronomers only observe these star-eating black holes for a short period of time after the TDE, which is why we're just now learning how often black holes burp up bits of their food.

"If you look years later, a very, very large fraction of these black holes that don't have radio emission at these early times will actually suddenly 'turn on' in radio waves," Yvette Cendes, a research associate at the Havard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and lead author on a new study told Live Science.

Of course, the term "burp" is used here to describe the process that happens after the TDE has passed when remnants of the star are literally ejected from the black hole. It's not the most scientific term by any means, but it is a good way to describe the situation. And this isn't the first time we've observed a black hole burping up a star's remains. This new research does expand on how often it happens, though.

A new study on these findings is available on the preprint server arXiv. The study has yet to be peer-reviewed by other scientists.