When scientists studying Mars discovered a massive landslide on the Red Planet they thought it looked familiar. The cascading material had carved long, curved ridges, and the area was eerily similar to some landslides that have been observed here on Earth. What made that comparison particularly exciting was the fact that on Earth, landslides like this are often associated with the presence of ice beneath the ground.

This, researchers believed, was a clue that something similar may have happened on Mars some 400 million years ago when the landslide is thought to have occurred. Since ice means water, and water means the potential for life, it was a tantalizing idea. Unfortunately, a new investigation suggests that ice and water may not have played a role after all.

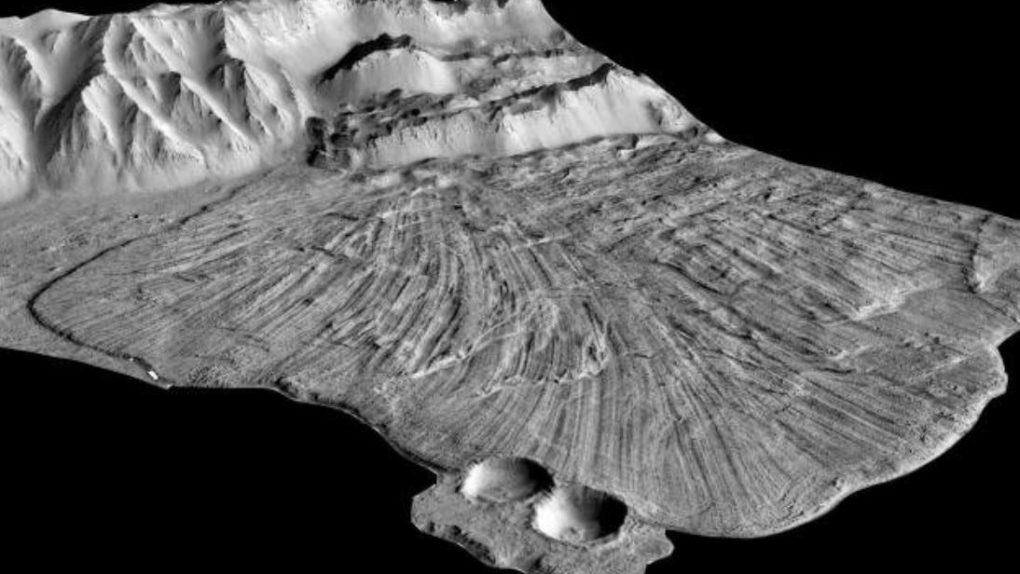

It had been thought that the unique landslide formations seen on Mars must have been created with the help of ice, but scientists wanted to be sure. So, using three-dimensional scans of the region as a starting point, scientists tested the possibility that such a feature could be created simply by a landslide moving at a particularly high speed.

What they found was that it would indeed be possible for the sprawling remnants of the landslide to have been produced by material tumbling down from high up on a Martian mountain. An unstable and rocky surface may have allowed such a landslide to reach speeds of well over 200 miles per hour, carrying the material vast distances and forming the unique ridges we see today.

“We’ve shown that ice is not a prerequisite for such geological structures on Mars, which can form on rough, rocky surfaces,” Giulia Magnarini, a Ph.D. student at University College London and first author of the paper, said in a statement. “This helps us better understand the shaping of Martian landscapes and has implications for how landslides form on other planetary bodies including Earth and the Moon.”