A New Study Says Humans Might Have The Genetic Capability To Spit Venom

All living creatures evolve over the years, adapting to their immediate living conditions in order to survive. That includes humans as well, who have evolved over millennia in response to various changes. Could humans ever become venomous if new living conditions make it necessary for our species to immobilize or slow down food sources with the help of self-secreted toxins? Researchers from Japan and Australia have figured out that the human body already has what it takes to develop that sort of capability. However, there's no guarantee that it'll ever happen. More importantly, the research might allow future studies to figure out answers to more pressing questions, such as how to stop cancer from growing in certain organs of the body.

"Essentially, we have all the building blocks in place," Agneesh Barua told Live Science when speaking about the new study. "Now it's up to evolution to take us there." Barua is a doctoral student in evolutionary genetics at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan and a co-author of the paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers didn't actually study the toxins necessary to label a species as venomous. Instead, they analyzed the "housekeeping" genes, the genes that are associated with venom but aren't responsible for the toxins. These regulatory genes are the basis of venom systems in animals.

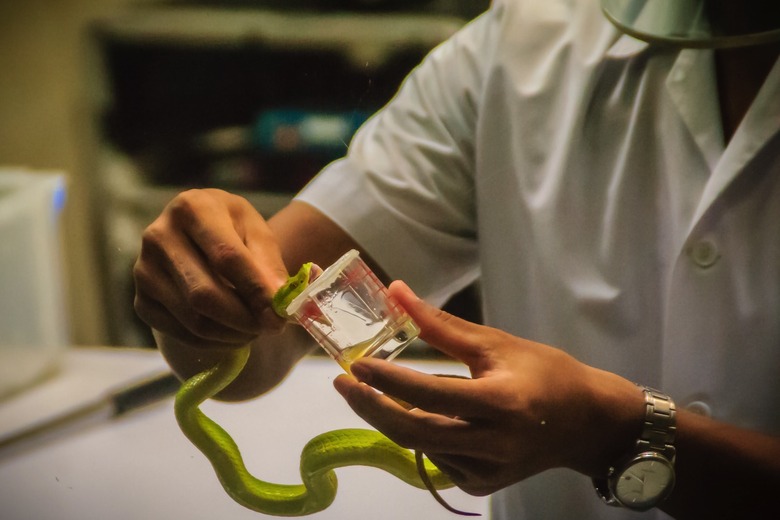

The team analyzed the genome of the Taiwan habu (Trimeresurus mucrosquamatus) brown pit viper to see which genes are associated with the venom system. They found many genes common in multiple body tissues of amniotes, or animals that fertilize eggs internally or lay eggs — reptiles, birds, and some mammals are included here. Many of these genes included something called folding proteins. Making toxins involves manufacturing or folding several different proteins. "A tissue like this really has to make sure that the protein it is producing is of high quality," Barua told the site.

The authors discovered that the same regulatory housekeeping genes are found in abundance in the human salivary gland, which produces a key protein of its own. Humans could theoretically manufacture their own toxins if the species evolved towards a path where this particular attack or defense mechanism would be required.

The report explains that humans and mice already produce a protein key to toxins in various venom systems. Called kallikreins, they're proteins that can digest other proteins, and they're secreted in saliva. This would be a starting point for humans to become venomous.

Humans do not need to be venomous because of the way we live. Over the thousands of years, we've developed the tools and social skills required to ensure access to food, whether it's hunting or growing it. There's no current need to have a secretable substance capable of annihilating a threat. Producing and storing venom might be an energy-intensive process as well, with Live Science citing an example from the animal kingdom where a species has regressed its ability to deliver venom. Sea snakes have vestigial venom glands that aren't active because they now feed on fish eggs rather than live fish.

Bryan Fry, a biochemist and venom expert at The University of Queensland in Australia who was not involved in the research, told the site that the research is "going to be a real landmark in the field. They've done an absolutely sensational job of some extraordinarily complex studies." But that's not because the researchers think that humans have the building blocks that would allow evolving into venomous species.

Understanding the genetics behind the control of venom could be key for various medical fields. He explained that if the cobra's brain started expressing the venom gland's genes, it would die of self-toxicity. This study might allow other researchers to learn how cancer evolves in various places, where tissue ends up growing out of control when it shouldn't. "The importance of this paper goes beyond just this field of study because it provides a starting platform for all of those kinds of interesting questions," Fry said.

The study is available at this link.