Newly-Discovered Fossilized School Of Fish Is Like A Snapshot In Time

Finding a single fossil of an animal that died some 50 million years ago is cool. Finding two? That's just plain awesome. But what about finding 259 of them at once? Well, there just isn't a word in the English language to describe that level of greatness.

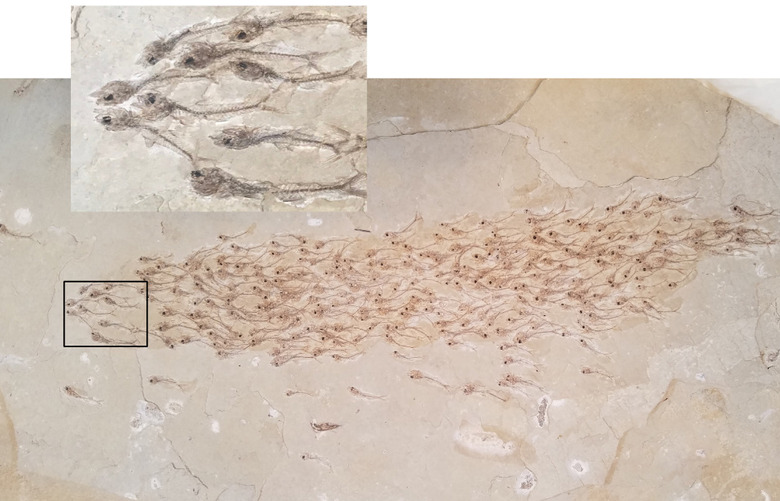

That's exactly what researchers from Arizona State University and Japan's Mizuta Memorial Museum uncovered hiding within a big chunk of limestone in the fossil hotspot known as the Green River Formation. The hundreds of tiny fossils are what's left of a school of tiny fish that happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and the discovery is helping scientists better understand how ancient fish behaved.

The discovery, which was written about in a new research paper published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, is like a window back in time. The tiny fish, some as small as 20 millimeters from tip to tail, appear to have been traveling in a shoal much like fish do today, and that's a big deal for researchers trying to paint a picture of how ancient species behaved.

Bones can only teach us so much about what long-extinct species were like, and trying to suss out clues to how they acted when alive can often be close to impossible. These pint-sized fish, which are thought to have been caught in a mass of collapsing sand in shallow water, were clearly banding together in a formation akin to what we see in small fish today, meaning that fish have been doing this for at least 50 million years.

"Collective motion by animal groups can emerge from simple rules that govern each individual's interactions with its neighbours. Studies of extant species have shown how such rules yield coordinated group behaviour, but little is known of their evolutionary origins or whether extinct group-living organisms used similar rules," the researchers write. "Our study highlights the possibility of exploring the social communication of extinct animals, which has been thought to leave no fossil record."