- Researchers this week have released a coronavirus update tied to the protests in major cities around the US this summer.

- Almost 40,000 people were surveyed to determine that there is a negative correlation between people who confirmed participating in a racial injustice protest this summer and a locality’s coronavirus cases.

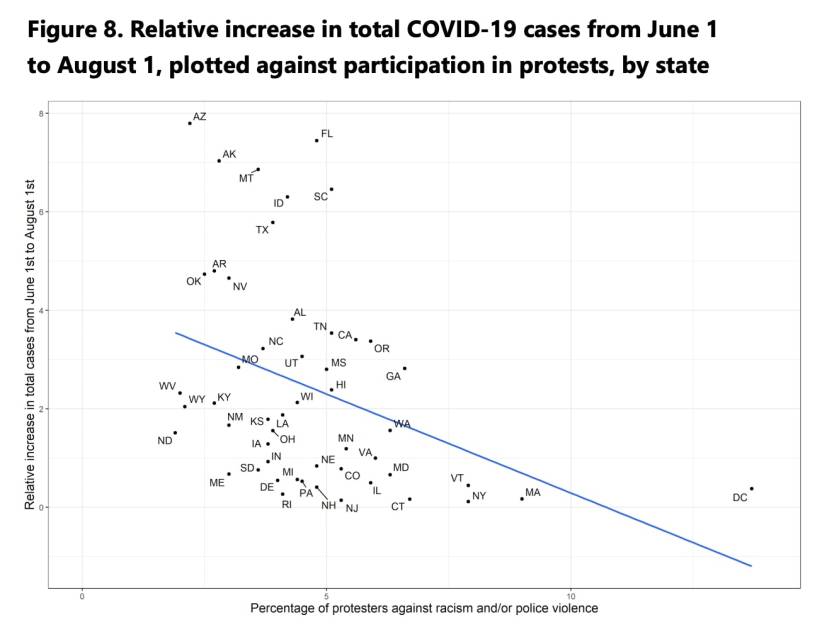

- From the report itself: “There is a clear and significant negative correlation between the percentage of a state’s population who reported protesting and the subsequent increase in cases of COVID-19.”

Here’s a coronavirus update that might surprise some of you — particularly those of you who thought that this summer’s protests largely stemming from the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd might spur an increase in local numbers of coronavirus cases. The logic seemed to be tied to the fact that the protests ignored one of the key elements of the public health guidance we’ve all been urged to follow for the last six months or so — social distancing, and not being in close proximity with people outside of one’s own household for an extended duration. Accordingly, I predicted here that President Trump might quickly move to dismiss the racial injustice protests by laying any surge in coronavirus cases at their feet.

Here’s what happened, instead.

New findings from a study encompassing almost 40,000 people have just been released by researchers from Northeastern, Harvard, Rutgers, and Northwestern universities, a study that takes a close look at the relationship between coronavirus case trends and the national demonstrations against issues including police brutality. The biggest takeaway from the study — which involved surveying 37,325 people across all 50 states plus Washington DC in June and July, and subsequently finding that almost 5% of all US adults participated in some kind of protest against racism and police violence this summer — was the following:

Per the report prepared about the findings, “There is a clear and significant negative correlation between the percentage of a state’s population who reported protesting and the subsequent increase in cases of COVID-19. Thus, for example, Washington DC, which had by far the highest reported participation rates in the protests at 13.7%, had a relatively low increase in cases during this period.” Interestingly, the data herein also indicates, among other things, that people in states with higher levels of protests also had higher levels of compliance with wearing face masks.

This study was only concerned with comparing levels of protest activity with coronavirus case data. It doesn’t identify definitive reasons for the negative correlation it found between the two, although there are suggestions that correlate with what health experts and bodies such as the World Health Organization have already disseminated. For example, organizations like the WHO, CDC, and others have already pointed to the dangers associated with congregating indoors, which increases the chance of being exposed to aerosolized coronavirus particles. These protests, of course, were outdoors, which may partially explain the findings.

“We’re not saying the protests didn’t cause more cases, an assessment that will require substantial, additional analyses,” said David Lazer, a professor of political science and computer and information sciences at Northeastern. “It’s just that if they were the key drivers, then you would expect the places that had the most protesters to have the biggest surge, and, in fact, the opposite is the case.”