- One of the strangest coronavirus symptoms is the loss of smell and taste.

- Scientists have explained how the virus infects the olfactory epithelium, revealing that the neurons responsible for sensing are not actually damaged in the process.

- A new report explains that the resulting localized inflammation can lead to residual nerve damage that may prolong anosmia. This explains why survivors take so long to regain their sense of smell.

One of the strangest symptoms associated with the novel coronavirus concerns the sense of smell. Doctors noticed in the first months of the pandemic that some COVID-19 patients complain of a sudden loss of smell and taste, and it became clear that the virus was responsible. Research proved that there is a correlation between the symptom and COVID-19, and anosmia is now a symptom doctors screen for. It’s also on the CDC’s COVID-19 information pages.

Not all people develop anosmia, however, so the symptom alone isn’t enough to confirm a diagnosis. Moreover, not all people recover their smell at the same speed once the disease has run its course. And a new report explains exactly what happens inside the nose once the virus invades.

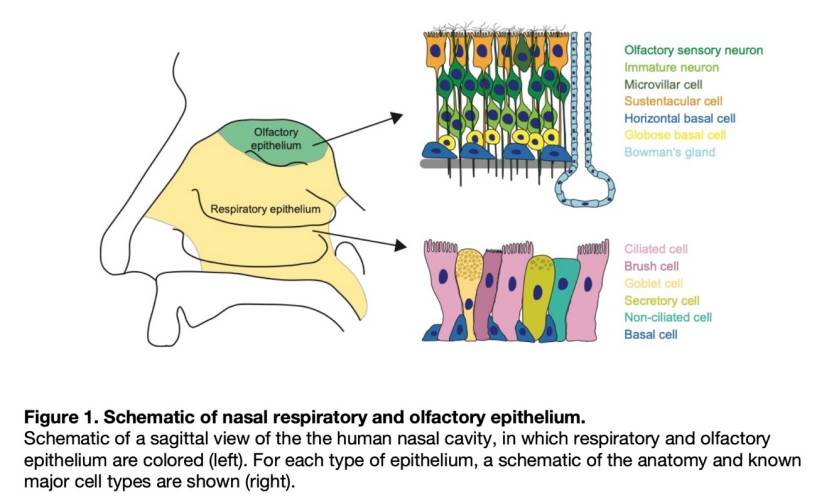

Researchers from Harvard published a study back in March that explains how the virus infects cells in the olfactory epithelium inside the nose. They looked at the genes of the cells and found that the virus doesn’t actually bind to the neurons that can sense smell. Instead, the virus infects support cells from the olfactory regions. More than a month later, a different study suggested that early COVID-19 screening tests should cover the olfactory epithelium. This could speed up the detection of cases, particularly asymptomatic people who might not exhibit loss of smell.

Citing the March study, two doctors co-wrote an article explaining the loss of smell in The Conversation a few days ago. The report doesn’t just explain the sudden loss of smell, but also why some people might take longer than others to regain their senses. Simon Gane and Jane Parker say that loss of smell may be common in colds caused by other coronaviruses. But that happens simply because of congestion. A blocked nose would prevent the smell from reaching the olfactory epithelium. Once the symptoms clear, smell returns immediately.

The novel coronavirus has a different pattern, and that’s because the nose doesn’t get blocked.

“Now that we have CT scans of the noses and sinuses of people with COVID-19 smell loss, we can see that the part of the nose that does the smelling, the olfactory cleft, is blocked with swollen soft tissue and mucus – known as a cleft syndrome. The rest of the nose and sinuses look normal, and patients have no problem breathing through their nose,” the two scientists wrote.

Gane is a consultant rhinologist and ENT surgeon at the University of London, while Parker is an associate professor of flavor chemistry at the University of Reading.

Noting the March research, Gane and Parker explain that it’s clear the virus infects the sustentacular support cells via the same ACE2 receptors. These proteins are found on these olfactory cells, the lung, and several other organs.

“We expect that these support cells are likely to be the ones that are damaged by the virus, and the immune response would cause swelling of the area but leave the olfactory neurons intact,” they said. “When the immune system has dealt with the virus, the swelling subsides, and the aroma molecules have a clear route to their undamaged receptors, and the sense of smell returns to normal.”

However, what’s unusual for some COVID-19 patients who experience anosmia is that they have to wait a few weeks after the symptoms disappear to start registering smell again. The explanation might have to do with the way the inflammation progresses. The neurons may not be damaged by the virus directly, but they can be affected by the inflammation in the area.

“Inflammation is the body’s response to damage and results in the release of chemicals that destroy the tissues involved,” the researchers theorize. “When this inflammation is severe, other nearby cells start to be damaged or destroyed by this ‘splash damage.’ We believe that accounts for the second stage, where the olfactory neurons are damaged.”

The olfactory neurons need time to regenerate from the supply of stem cells inside the lining of the nose, Gane and Parker wrote. That’s why the recovery of smell may be prolonged and why smell could be distorted initially. That is, you might associate different smells to the same substances, a symptom known as parosmia.

The researchers say this strange COVID-19 symptom will encourage more people to study this particular sense, which has often been overlooked.