- NASA is doing everything it can to avoid bringing Earthly organisms to other worlds, but what if we should be doing the opposite?

- Seeding other worlds with life could potentially have big benefits for humanity in the distant future.

- Icy moons like Enceladus may already host alien life.

If you’ve never seen the movie Prometheus — the prequel-to-the-prequel of the original Alien film — let me tell you how it begins, and why it might be the perfect analog for mankind’s current conundrum. We’re shown a rocky, watery planet devoid of animal life. Clouds tower overhead and vast lakes and oceans are filled by turbulent rivers, and the world appears to be ripe for habitation, at least by human standards.

Then we see him. A humanoid being we’re led to believe arrived via a large spacecraft stands beside a raging river. He disrobes, revealing a body that appears nearly human, but not quite. Then he drinks a strange goo and immediately suffers grave consequences. We see his body quite literally disintegrate as his DNA breaks down. His remains tumble down a waterfall and we’re treated to a microscopic view of new DNA strands forming, fresh cells dividing, and, presumably, new life taking root.

When you make it through the rest of the film you’ll eventually come to the conclusion that the planet we saw was likely Earth, and that the alien creature — called an “Engineer” in Alien lore — made the ultimate sacrifice in order to seed our planet with the building blocks of life.

It’s not the most glamorous end for the Engineer, but it’s how director Ridley Scott decided to show a fictionalized history of the beginnings of life on Earth. Prometheus is of course pure fiction, but in our current reality, we stand at a crossroads where we can choose between two paths, one of which is not dissimilar from the sacrifice we see in the movie.

To Seed or Not to Seed

NASA recently updated its Planetary Protection policies

in advance of the inevitable crewed missions to the Moon as well as Mars. The policies are strict and reflect the space agency’s stance that mankind should do whatever it takes to prevent Earthly contaminates — microbes or any other form of organic life—from tagging along as we explore the cosmos.

Generally speaking, scientists support the idea that we should keep other worlds as pristine as they are when we arrive… but what if we didn’t? What if our obligation isn’t to prevent the spread of life, but to encourage it?

NASA has a very good reason for not wanting to bring bacteria and viruses to other planets. The fact that we have yet to find life on other worlds means that, as we explore, we need to prevent accidental contamination to ensure that when we finally make that discovery, we know it’s the real deal. If we were more laid back in our approach to space exploration, we might “discover” a microbe on the surface of Mars that we brought with us.

Those kinds of false positives are bad for science, but what does that say about mankind’s stance on seeding other worlds with new life?

Another Earth

NASA may have policies to prevent life from tagging along as we travel to new worlds, but the space agency and other scientific organizations around the world are actively working on ways in which we might use the soil of Mars or other worlds to grow crops. The idea is that if humans ever hope to set up shop on the Red Planet, they’re going to need to grow their own food at some point, and that means growing the first alien plants and vegetables.

This could be done by taking Martian soil and bringing it into a sort of isolated greenhouse, which would mean we’re not really growing anything on Mars or seeding it with life. This technique will likely be required, especially early on, as Mars’ thin atmosphere and extreme temperatures could easily kill off anything we wanted to grow in an exposed area. There’s not a lot that grows in -80 degrees Fahrenheit, after all.

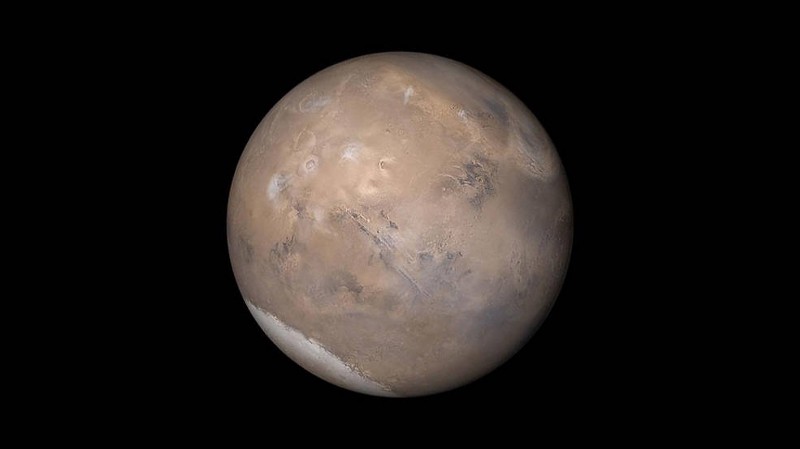

But if we look a bit further into the future, there are some, like SpaceX boss Elon Musk, who believe that transforming Mars to be more Earth-like—a process called terraforming—is not only possible but inevitable. That would mean bolstering the atmosphere, raising the temperature of the planet, and spreading plant life far and wide.

Where Water Flows

Getting Mars in shape to support life would take a long, long time. We don’t know exactly how long because we’ve never done it before, but transforming the planet into a second Earth would almost certainly take decades or even a century or two, and that’s assuming we make some big technological advances in the meantime. NASA is of the opinion that it’s not even possible with current technology, but that could change in the future.

However, there are other worlds in our solar system that not only may already contain life but could potentially host Earthly life right now if we were inclined to make the trip. Enceladus, an icy moon of Saturn, was once thought to be a frozen chunk of ice and nothing more. We now know that there’s liquid water hiding deep beneath the frosty crust, and a subsurface ocean remains warm enough that water flows, and that means the potential for alien life.

It also means that, since we know of many organisms that can survive in frigid water and in the absence of sunlight, we could seed that subsurface ocean with life from Earth.

“Multiple discoveries have increased our understanding of Enceladus, including the plume venting from its south pole; hydrocarbons in the plume; a global, salty ocean and hydrothermal vents on the seafloor. They all point to the possibility of a habitable ocean world well beyond Earth’s habitable zone. Planetary scientists now have Enceladus to consider as a possible habitat for life.” — Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

How we might go about transplanting species from Earth to Enceladus is anyone’s guess—again, this kind of thing hasn’t even been widely considered before — but it would likely involve many separate missions to piece together a fledgling ecosystem until it can sustain itself. That’s a monumental task and one that might not have any real benefit for mankind in the short term.

The other big question is, if we visit Enceladus (or any other world, for that matter) and don’t immediately find life, how sure would we have to be before deciding to seed Earthly life there? A single mission to poke our heads beneath the ice of Enceladus and look around might not reveal much, but if we were to intentionally bring Earthly organisms and spread them throughout the watery world they could push away or even eradicate true alien life that we simply hadn’t managed to detect. It would be a bit like carrying an invasive species from one continent to another, but in this case, we’d be compromising an entire world.

Can mankind be trusted?

Perhaps the best argument against the idea of seeding other worlds with Earthly life is the fact that mankind hasn’t proven that it can handle the seemingly straightforward task of not destroying its own home planet.

We’re really, really good at messing things up, and despite scientists warning us that we’re rapidly approaching an inevitable tipping point, we haven’t done enough to slow climate change. Ocean waters are warming, reefs are dying of the equivalent of heat stroke, and storms are getting stronger. The data is all there, and most people choose to either ignore it or, if they do acknowledge it, they fail to make changes in their own lives that could turn the tide.

One of the reasons the idea of terraforming Mars might sound so appealing is that it could offer a fresh start. If we can’t save Earth from our own poor decisions, an unspoiled world capable of supporting life might eventually be necessary if we hope to persist as a species. It’s a frightening thought, to be sure, but it’s slowly becoming a reality.

As for seeding life to a place like Enceladus, if we set aside the ethical debate of sullying another world with Earthly organisms, we’d still need a really good reason to actually do so. Those reasons may already exist. Could we eventually turn Enceladus into a futuristic fish farm? A water world offering a virtually unlimited bounty of sustainable food for us back on Earth sure sounds appealing and might be just what we need as our planet’s booming human population puts more and more strain on the global food supply. The logistics of such a program are mind-bending and certainly not possible today, but in the future? Who’s to say food supply chains shouldn’t extend to space?

These are questions that are only recently being asked, but we may need to come up with the answers sooner than we’d like. Human lives are, unfortunately, quite short. Safeguarding human existence for generations hundreds or even thousands of years in the future means working toward goals we’ll never live to see accomplished. For a species that craves gratification in all forms, that’s not an easy pill to swallow, but it’s something we’ll have to grapple with sooner or later.

The Two Paths

As it stands, the decision of whether we should be willing to seed life to other worlds comes down to whether or not we believe we actually need to do so. If we require a “second Earth” because we ruin the first one, mankind’s knack for survival suggests we’d find a way to make it happen, or die trying.

The question of whether we should seed life throughout our solar system simply because we can is much more complicated. The debate touches on notions of “playing God” and there are nuances that simply can’t be fully explored by one person alone.

At present, no space agency, country, or legitimate scientific group appears willing to entertain the idea that spreading life could have a big upside at some point down the road, even if none of us would be around to reap the benefits. For now, it’s a fun thought experiment, but when crewed missions begin trips to Mars — a possibility as early as the 2030s—these questions will take on greater meaning, and it may not be long before we’re forced to reckon with our willingness (or lack thereof) to spread Earth’s gift of life elsewhere.