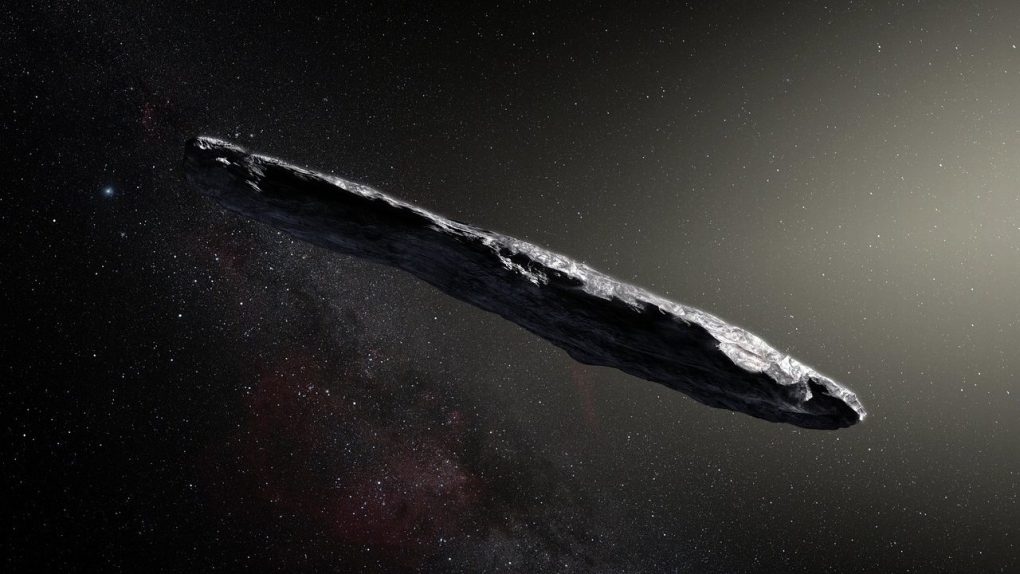

In 2017, our solar system received its first interstellar visitor, an unknown object named ‘Oumuamua. The massive visitor was believed to be over 300 feet long and baffled scientists. Somehow, the massive rock accelerated, though no signs of a comet trail were detected. This led some to believe ‘Oumuamua may have been alien in nature. However, a new study could put all those beliefs to rest once and for all.

The new study, which researchers published in Nature, claims that the strange movements astronomers observed from ‘Oumuamua may have been caused by the release of hydrogen reserves trapped in water ice on the object.

It’s a very logical conclusion, especially considering the likelihood that ‘Oumuamua was an alien probe as some believe it to have been. Aside from the strange acceleration astronomers observed, there is no other indication from the object that this was the case. For all intents and purposes beyond that, though, the cosmic object acted like any other comet humanity has observed.

While some have jumped at the chance to call ‘Oumuamua an alien spacecraft, others have tried to look at the object from a much more realistic approach. Many scientists proposed that it could have been mostly made up of hydrogen ice. The theory here is that as the object moved closer to our Sun, it began to warm, releasing the trapped hydrogen inside and accelerating it along its orbit.

To test the theory, the researchers involved with the new study looked at how water ice with hydrogen trapped within it would react to being warmed by radiation. The researchers examined whether ‘Oumuamua was large enough to trap enough hydrogen for the observed acceleration and whether the release of that trapped hydrogen by water-ice melting would account for what was seen.

The researchers found that not only was the object large enough to hold that much hydrogen trapped within its water ice, but the release of said hydrogen could have caused the way that ‘Oumuamua accelerated through our solar system.

But if the object was releasing trapped hydrogen, why didn’t astronomers notice it? Well, because they weren’t looking for hydrogen outgassing. And, even if they had been looking, the study says that the levels associated with this type of release would not have been detectable from Earth-based observatories.