Finding new planets lurking in space isn’t as hard as it used to be, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a challenge. High-tech instruments like NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope have provided researchers with a wealth of data that can be mined for new discoveries. University of British Columbia student Michelle Kunimoto did just that, and now has 17 brand new planets to her name.

Kunimoto, a Ph.D. candidate, is the lead author of a new paper published in The Astronomical Journal that describes the 17 new planets in rough detail. We don’t know much about them, but at least one of them is approximately Earth-sized, and is thought to be rocky, just like our own planet.

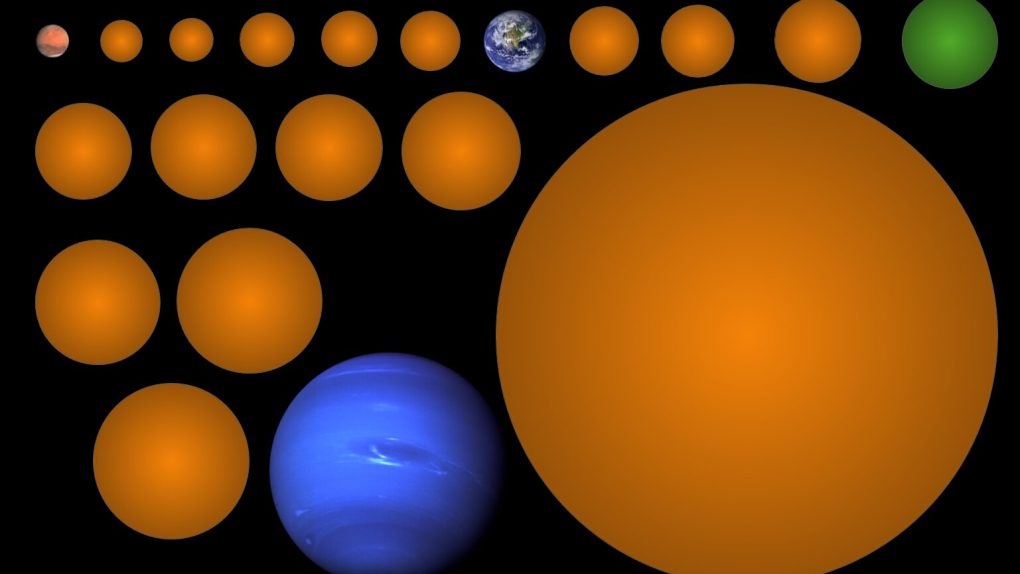

Many of the 17 planets are quite large, and are thought to be mostly gas. There are lots and lots of gas planets out there, but finding smaller, rocky worlds has proven more difficult for astronomers. The planet now labeled KIC-7340288 b is around 50% larger than Earth, and it happens to be in the so-called “Goldilocks” zone of its star, meaning that it may be warm enough on its surface to support liquid water.

“This planet is about a thousand light years away, so we’re not getting there anytime soon!” Kunimoto said in a statement. “But this is a really exciting find, since there have only been 15 small, confirmed planets in the Habitable Zone found in Kepler data so far.”

The discoveries were made using a technique that has become popular amongst exoplanet hunters in which the light of a star is observed closely for changes in brightness. When a star’s brightness temporarily fades, it indicates something passing in front of the star, from Earth’s perspective. These passes, called transits, can tell astronomers a surprising amount about the objects orbiting a star.

Details such as how long it takes the planet to complete an orbit and how much light it blocks as it passes in front of the star offer clues to its size and orbit. Astronomers can make a few assumptions based on that data, and paint a clearer picture of what is lurking out in the cosmos.