- A standard coronavirus treatment is still unavailable, although researchers have made significant progress at developing new protocols for existing drugs and adapting them for COVID-19. Promising new drugs and vaccines are also in the works.

- The search for a COVID-19 cure has prompted scientists in Spain to study existing meds and see whether they can inhibit the coronavirus’s ability to replicate inside the body.

- The researchers identified seven molecules out of more than 6,400 drugs, including Xanax, a widely used anti-anxiety treatment.

The novel coronavirus pandemic brought plenty of sorrow and pain, as we learned how devastating COVID-19 can be. But there’s been plenty of good in all of this, and that doesn’t have to go unnoticed. It’s not just what the armies of doctors and first responders have been doing for the past few months, but also the immense amount of work that researchers put into studying SARS-CoV-2 to find ways to limit the transmission, and cure COVID-19 much faster than what is currently possible. Therapy protocols are already being used successfully around the world to save patients. Plasma transfusions work and antibody-based drugs are in the works. Several vaccine trials have progressed faster than we would have imagined, and the world is optimistic about their chances of success.

The work hasn’t stopped there, as researchers are still trying to figure out how to neutralize the virus once it infects the body. Scientists have looked at specific characteristics in meds that could hinder the virus’s ability to replicate inside cells, and they have shortlisted seven existing human and animal drugs that might do the trick. The list includes the extremely common anxiety drug Alprazolam (Xanax), as well as six other meds, two of which have already shown promising results in labs.

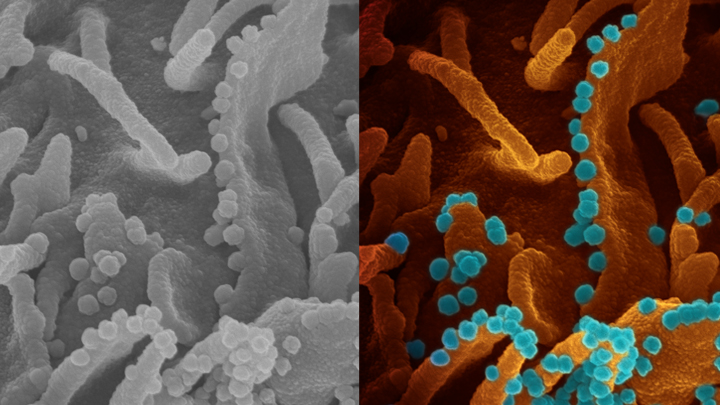

Researchers from universities around Barcelona, Spain searched for existing drugs that could block the main protease (M-pro) of the virus, which plays a key role in the whole replication process. The coronavirus binds to cells via ACE2 receptors and takes over the cell to manufacture replicas. The cell dies in the process, and the new copies of the virus can infect other nearby cells. Most immune systems can put up a fight, whether they’re helped by drugs or not. But some people can’t fight the disease well enough, or the immune response is exacerbated and can lead to death.

Stopping the virus from binding to cells is something monoclonal antibodies drugs will do, as will post-COVID-19 immunity. But drugs that can limit the virus’s ability to replicate could also help in future therapies.

The team analyzed 6,466 drugs that are authorized for use, looking for the ones that can inhibit the M-pro enzyme. The researchers used a computational screening method to isolate the approved drugs that could work in COVID-19 therapies, Knowridge reports. The research predicted seven drugs could act as inhibitors, including perampanel, carprofen, celecoxib, alprazolam, trovafloxacin, sarafloxacin, and ethyl biscoumacetate. Some people will instantly recognize a few of these drugs because they might be using them for themselves or their pets. Alprazolam might stand out of the pack, as that’s the generic name of Xanax, a well-known anxiety treatment that is used by millions.

Ethyl biscoumacetate is also a highlight because it’s a drug that can be used as an anticoagulant. Separate studies have shown that COVID-19 leads to severe blood clotting and potentially life-threatening complications, including strokes and heart attacks.

Trovafloxacin and sarafloxacin are antibiotics, and perampanel is an antiepileptic.

But what the researchers ended up testing in labs are carprofen and celecoxib, both nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drugs. The only real difference between these drugs is that the former is for animal use. What’s interesting is that some doctors said a few months ago that NSAIDs could be a risk factor for COVID-19, although research that followed indicated that isn’t the case at all.

The Spanish researchers have shared the results with the international initiative COVID Moonshot, which selected the NSAIDs above for testing.

The results found that just 50 μM of celecoxib or carprofen would be enough to inhibit the in-vitro activity of M-pro by 11.90% and 3.97%, respectively. Both molecules could be used in the future for therapies, although more research will be required.

The remaining drugs could be tested soon, Knowridge says. That said, there’s no proof that Xanax might improve the condition of COVID-19 patients or that it can prevent a severe outcome. The same goes for the other meds mentioned above, if they’re still available to consumers — sarafloxacin was discontinued in 2001, and carprofen is for veterinary use. Xanax might be the most used molecule of the seven, though it’s a drug that can have serious side-effects when combined with other substances, including alcohol.

One of the things scientists are also looking at is the drug-drug chemical reactions that may appear in COVID-19 patients, where the meds for an underlying condition could interact with the experimental drugs that are studied. Undark has a great article on the subject, describing the various potential drug interactions. Widely prescribed medications in psychiatry such as Xanax can also be highly interactive with some other COVID-19 therapies being tested.