Researchers have been heavily studying the possibility of de-aging cells for over the last ten years. Now, a group of researchers in the U.K have developed a new de-aging technique that can reverse aging in cells as far back as 30 years.

This new de-aging technique produces better results than we’ve ever seen before

The new technique was developed by Diljeet Gill and his colleagues. Gill is a postdoctoral candidate at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge. The researchers involved published a study on the technique in the journal eLife in early April. They call the new de-aging technique “maturation phase transient reprogramming.”

The researchers tested the de-aging technique on a common type of skin cell called fibroblasts. They gathered the cells from three middle-aged donors, whose age averaged out to around 50 years old. After applying the technique, they compared those older cells to cells taken from donors between 20 and 22 years of age. The researchers found that both sets of cells were very similar chemically and genetically.

They also discovered that the technique affected the same genes that are affected by age-related diseases. This includes genes that are affected by Alzheimer’s disease and even cataracts, which often form as people age.

Acting like younger cells

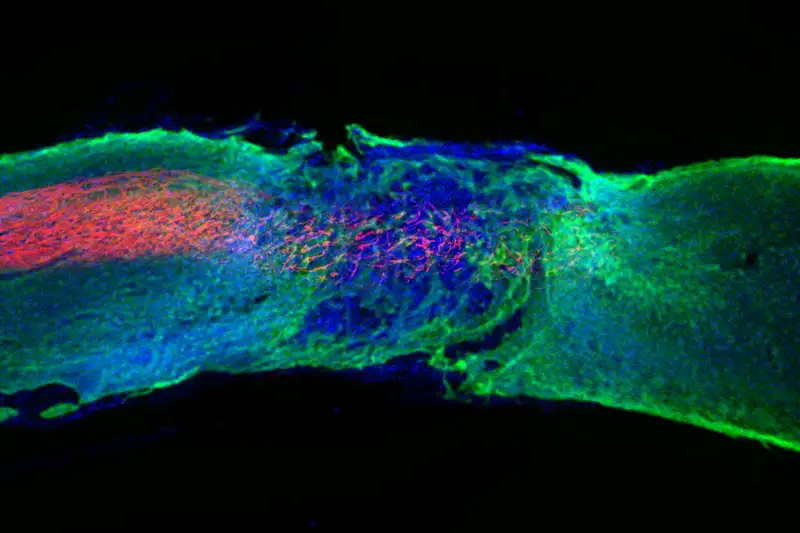

But the research on the de-aging technique doesn’t stop there. Gill and his colleagues also wanted to see if the fibroblasts from the older donors would act like the younger cells. To test this, the researchers wounded a layer of the cells. Afterward, they found that the now rejuvenated cells quickly moved to fill in the gap. This was similar to how younger cells act when they are wounded.

Of course, this isn’t the first study to show positive results from a de-aging technique. Scientists have been studying the possibility of reversing age for years now. In fact, some high-profile scientists even say we’re less than 20 years from being able to stop aging.

Many of these de-aging techniques rely on a method known as Yamanaka’s method. However, there are some key differences between that method and this new one that Gill and his colleagues have developed. Yamanaka’s method completely reprograms the cells. This causes them to lose their identity and any specialized cell functions.

Gill’s method only partially reprograms the cells. This way they retain their purpose and specializations. This makes them less likely to turn cancerous when implanted in the body, too.

“Our results represent a big step forward in our understanding of cell reprogramming,” Gill explains in a statement. He says that the research has proved that we can rejuvenate cells without them losing their functions. This data could further play an important role in how scientists look into de-aging techniques in the future.