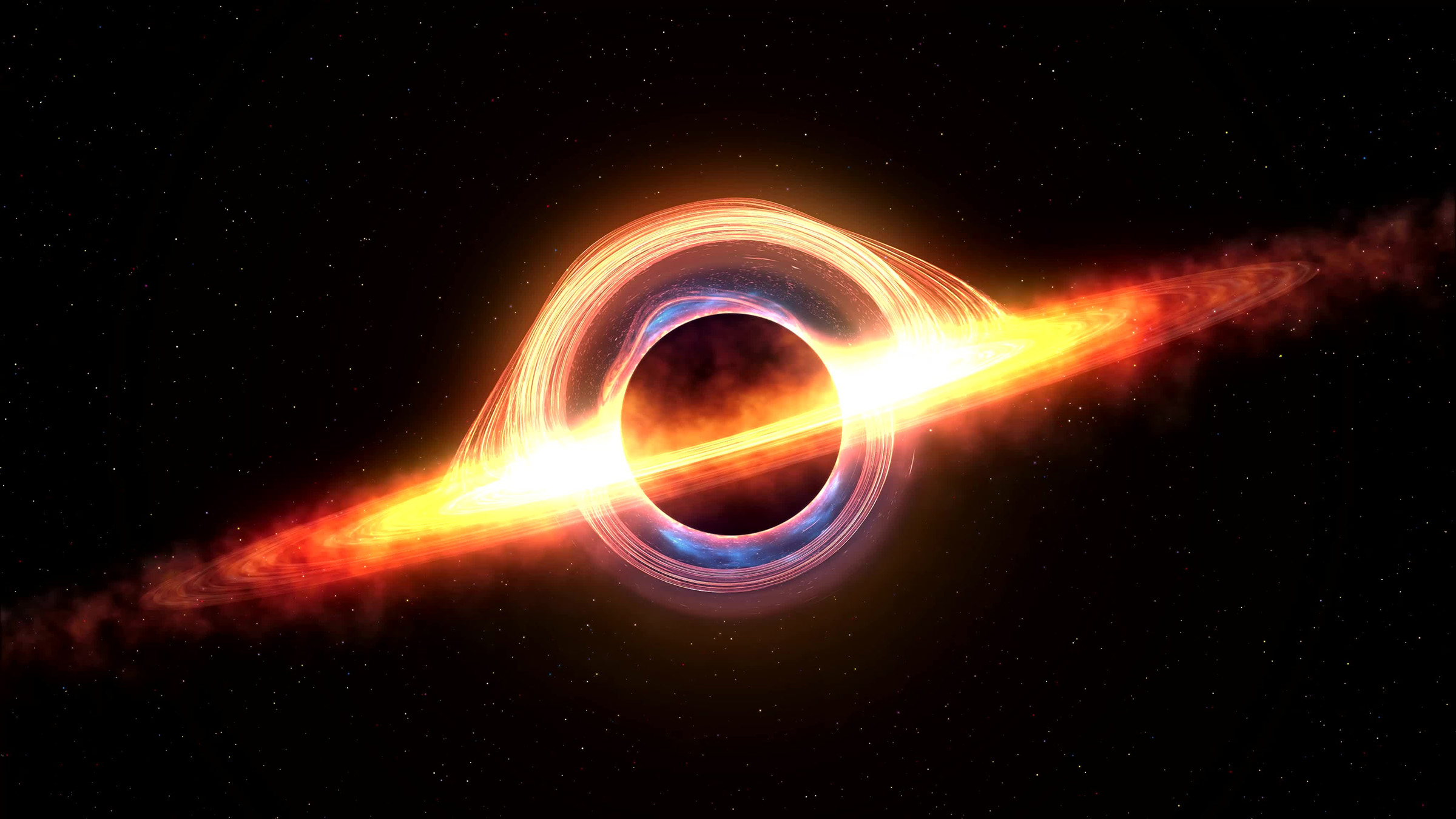

Researchers Say Some Black Holes May Be Kinks In The Fabric Of Space-Time

Black holes just got a lot more intriguing. According to new research, some black holes found in the universe may be kinks in space-time, tangles of light that aren't actually black holes, but instead are theoretical objects known as "topological solitons."

These theoretical kinks in the fabric of space-time could be lurking all around our universe, new research published in Physical Review D suggests. This new research was published in April and aims to push our understanding of quantum physics to new places.

Black holes are incredibly frustrating because of how dangerous they are and because the infinity point believed to exist within a black hole – the point that continues to suck things into it infinitely, never releasing it – isn't really possible. As such, we have something that explains that black holes can exist – the theory of relativity – but nothing to explain how they work.

In other words, we don't have the full picture when it comes to black holes, and we know that this impossible infinity point that seems to exist in black holes needs to be replaced by something more reasonable. Something that can actually exist. That's where topological solitons come into play. These kinks in the fabric of space-time could help us better understand the gravity black holes rely on.

By understanding that, we'd be able to understand better exactly how black holes work, and possibly decode the point that draws the gravity into the black hole itself. The problem is we don't have any black holes we can easily approach and study, and if we get too close, we risk whatever spacecraft we're using being sucked into it, thus being unretrievable.

This new study seems to offer a bit of groundwork toward helping us better understand black holes and the possible kinks in space-time that exist in that same vein. However, without any proper way to study or prove this research, it's just all theoretical at this point.

Perhaps in the future, we'll find a black hole that we can more easily reach, allowing for more in-depth research into such things. Scientists may also be able to use gravitational waves to peer into black holes, which could help answer some of our questions, too.