NASA’s Juno spacecraft has spent much of the past four years gazing at the massive gas giant Jupiter. The orbiter’s primary goal is to teach scientists as much about Jupiter as possible, but it’s also spent some time observing Jupiter’s many moons. Ganymede is the largest moon of Jupiter and also the largest moon in the solar system, so when NASA announced it would be directing Juno to observe Ganymede for the first time, it was a pretty big deal.

Now, we have the very first images that were captured during that flyby, and they’re absolutely awesome. The last time any spacecraft got so close to Ganymede was way back in the year 2000 when NASA’s Galileo made a relatively close flyby of the giant moon. Juno is an entirely different piece of hardware, and in many ways, it’s more advanced, so these new images are our best look at the moon that we’ve ever gotten.

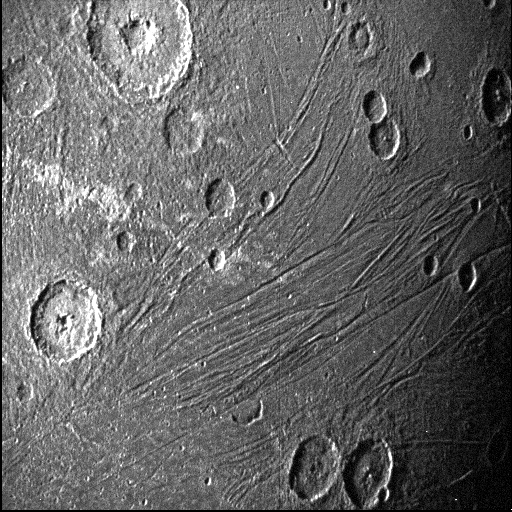

So far, Juno has sent back two photos that it snapped during its flyby of Ganymede. More will come, but these two initial snapshots are already enough to get us pretty excited. They show the massive, icy moon in stunning detail, revealing massive craters and dramatic lines stretching across the surface in every direction.

Ganymede is of particular interest to scientists due to the fact that it likely houses a vast ocean of liquid water deep beneath its surface. Inside its icy shell, tidal forces generate heat and ensure that the water never freezes. This combination of liquid water and readily available energy in the form of heat means that the potential for life may exist within the moon.

“This is the closest any spacecraft has come to this mammoth moon in a generation,” Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton said in a statement. “We are going to take our time before we draw any scientific conclusions, but until then we can simply marvel at this celestial wonder – the only moon in our solar system bigger than the planet Mercury.”

In addition to being the largest moon in our entire solar system, Ganymede is also the only moon with its own magnetic field. Scientists don’t know how important a magnetic field might be when it comes to providing a safe haven for life to take root, but they’re eager to find out.

Ganymede’s size makes it an interesting potential target for future missions that might seek to explore its subsurface ocean in search of extraterrestrial life. We know that life can exist in the absence of sunlight — many organisms on Earth do just that — but we don’t know if it’s possible for life to emerge in those conditions. It’s possible that early life requires light in order to form, but can adapt to darkness over time. Not finding life on Ganymede wouldn’t necessarily answer that question, but finding it most certainly would.