Promising Coronavirus Vaccine Might Be Delayed Because Not Enough People Are Getting Sick

- One of the coronavirus vaccine candidates that has shown encouraging results is the one being developed at Oxford, which could be ready for emergency use this September.

- However, researchers are running into a potential issue with testing, as there might not be enough COVID-19 cases in the UK to actually see if the vaccine works during the late stages of the human trial.

- Delays in research could lead to a postponed "launch" for the coronavirus drug, assuming it is actually effective and safe for humans.

If you've been following news about the evolution of the novel coronavirus pandemic, chances are that you've heard about Moderna, Oxford, CanSino, and BioNTech, which have all reached human trials with their coronavirus vaccine candidates, and have been featured in plenty of reports in the past few weeks. More than 100 labs are looking to develop coronavirus vaccines, and at least eight of them are in various phases of clinical trials.

Moderna and Oxford are easily the two most talked about vaccine candidates right now. The former made a partial announcement about human testing that raised some eyebrows, especially after word got out that several company officials executed pre-planned stock sales around the announcement. That doesn't mean Moderna's vaccine doesn't work or won't be ready in a potentially record time. It just paints the company in a less flattering light. The Oxford vaccine, on the other hand, might be deployed as soon as this September, with both Britain and the US having secured manufacturing capacity for the drug. However, the researchers might have to delay their vaccine because they're running into a bizarre problem. Just as they're recruiting more volunteers for the advanced phases of the research, there's not enough COVID-19 to go around.

The researchers already produced a first study that shows the vaccine works in monkeys. It's both effective and safe for the subjects, and that's why they moved to clinical trials. The results for Phase 1 should be available soon, with the first conclusions on human testing.

The Oxford team is now gearing up to recruit as many as 10,000 people for the next phase, half of which will receive ZD1222 (previously known as ChAdOx1 nCoV-19), and half of which will get a placebo. But professor Adrian Hill, the director of the Jenner Institute who embarked on this unexpected COVID-19 vaccination journey, worries that there aren't enough infected people out there for the study to yield results.

If the volunteers aren't exposed to the virus, whether they get the vaccine or the placebo, there won't be enough data for the study, and the vaccine could be delayed.

"It is a race, yes. But it's not a race against the other guys. It's a race against the virus disappearing, and against time," Hill told The Telegraph. "We said earlier in the year that there was an 80 percent chance of developing an effective vaccine by September. But at the moment, there's a 50 percent chance that we get no result at all."

"We're in the bizarre position of wanting COVID to stay, at least for a little while. But cases are declining," he said, warning that success isn't guaranteed to begin with. "I wouldn't book a holiday in October on the back of these announcements, put it that way," he said, referring to the slew of recent announcements about the Oxford vaccine.

The UK said a few days ago that it will get as many as 30 million doses for its citizens. Then the US announced a $1.2 billion investment in Oxford's partner AstraZeneca that would guarantee a supply of 300 million doses. Separately, AstraZeneca is in talks with other countries, including India, which could manufacture as many as 400 million doses via the Serum Institute, the world's largest vaccine producer.

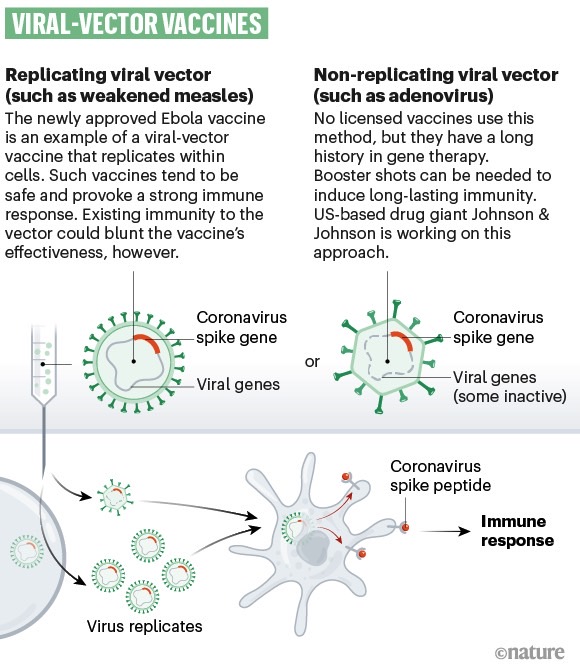

A type of technology used to create vaccines for infectious diseases.

Hill also said that it has secured assurances that the wealthiest countries of the world will not be the only ones to benefit from a successful vaccine and that there will be supply for others.

"I've been thinking about it day and night for weeks. We care about Africa. We know the people there. We know there's going to be a significant problem at some stage. Brazil looks terrible, and India is getting there fast," he said.

"The vaccine should be supplied to the countries of greatest need at the moment that it works, rather than the countries who got there first. And that will happen."

Oxford isn't alone facing this temporary disappearance of COVID-19 cases. "You think we've got a problem?" Hill said. "What would you do if you were in China? There are three Chinese companies looking for phase three, and there's no COVID in China. So what do they do?"

Indeed, reports a few weeks ago said that China was looking to other markets for vaccine testing. And one of the Chinese candidates will be tested in Canada.

One solution for Oxford's problem could be the controversial challenge trials that the WHO has approved not long ago. These are trials where volunteers are infected with the pathogen after the vaccine injection to observe the results.

Oxford's professor Andrew Pollard, who is also working on the project, told The Guardian a few weeks ago that there is "huge interest" in the possibility of challenge trials among those working on coronavirus vaccines, foreseeing a scenario where there wouldn't be enough disease around.

"At the moment, because we don't have a rescue therapy, we have to approach challenge studies extremely cautiously," Pollard said. "But I don't think it should be ruled out because, particularly in a situation where it's very difficult to assess some of the new vaccines coming along because there's not much disease around, it could be one of the ways we could get that answer more quickly."

Oxford has arranged trials in other countries as well, The Telegraph notes. But that could further delay the availability of results required to green-light mass-manufacturing.

As fast and as promising these vaccine candidates have moved, there's no guarantee everything will work, Hill warned, ZD1222 included. Therefore, that potential September "launch date" for the vaccine might slip further, assuming the vaccine passes all the scientific hurdles.

"Thirty million doses is quite hard, and one hundred million is harder still by September," the professor said. "Remember, even if we get a result in August, we can't start vaccinating everyone the next day."