Researchers Find Ancient 'Hell Ant' Frozen In Time, Locked In Battle

- Researchers have discovered an insect that lived nearly 100 million years ago encased in amber.

- The so-called "Hell Ant" had vertical jaws that it used to pin its prey against its horn-covered head.

- The incredible specimen is locked in battle and frozen in time with its prey in its jaws.

There are a seemingly countless number of different ant species on Earth today. They range from mundane and unthreatening to incredibly aggressive and even potentially deadly. Nearly 100 million years ago, ants roamed the Earth just like they do today, and researchers just found a specimen of one species that reveals how appropriate its nickname "Hell Ant" really is.

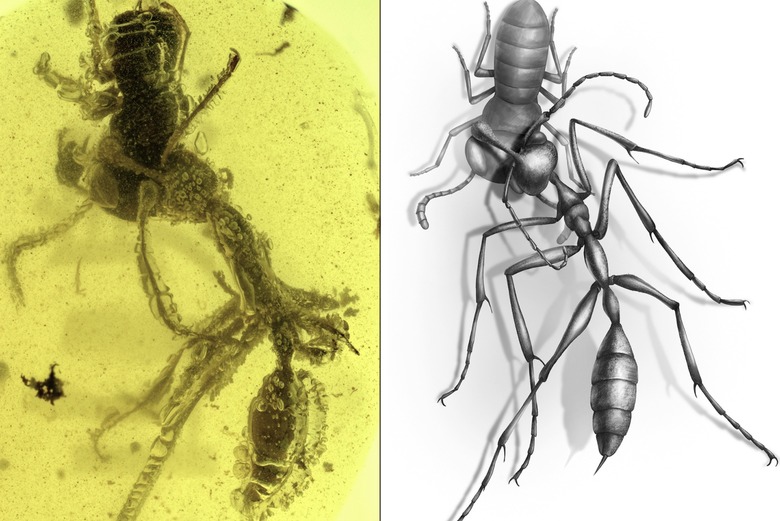

In a chunk of fossilized tree sap, called amber, a hell ant is seen locked in a battle with another ancient insect. Already known to science, the hell ant's head is particularly unusual. Rather than a pair of jaws situated horizontally as with most modern ants, the hell ant had a massive vertical jaw that we now know it used to snag its prey and slam them into spikes situated on its forehead.

The discovery of the fossilized hell ant and its prey is the subject of a new paper in Current Biology. The paper explains that the ant and its prey, frozen in time, have revealed how the hell ant preyed on its fellow bugs.

"We report a remarkable instance of fossilized predation that provides direct evidence for the function of dorsoventrally expanded mandibles and elaborate horns," the researchers write. "Our findings confirm the hypothesis that hell ants captured other arthropods between mandible and horn in a manner that could only be achieved by articulating their mouthparts in an axial plane perpendicular to that of modern ants."

The finding is incredibly interesting for a number of reasons, but the biggest one is that it adds to the scientific knowledge of how these ancient insects thrived. The fact that we don't see ants with similar features today may be an indication that something changed that made this method of snatching prey less viable. Scientists can only hope to piece together the history of the ant family tree by gathering as much information on various species as possible.

"As paleontologists, we speculate about the function of ancient adaptations using available evidence, but to see an extinct predator caught in the act of capturing its prey is invaluable," Phillip Barden, lead author of the study, said in a statement. "The only way for prey to be captured in such an arrangement is for the ant mouthparts to move up and downward in a direction unlike that of all living ants and nearly all insects."

It's definitely an interesting and unique discovery, not to mention incredibly rare, but it offers us a tiny glimpse into what the world was like 100 million years ago.