Netflix's New Boy Band Docuseries Uses AI To Bring A Con Man Back From The Dead

I have certain expectations whenever I sit down to watch a Netflix documentary or docuseries. One of them, and I don't think it's all that unreasonable, is that the story presented should be ... hold on to your seats here, folks! ... a true story, and supported by a preserved record of interviews, firsthand sources, documentation, and the like. Not, in other words, bolstered by archival footage and photos that've been manipulated by AI so that the director can make whatever point that they want to make.

Unfortunately, the latter has actually happened with Netflix documentary releases at least twice that I know of — since April!

We've already talked about one such instance. It's the use of generative AI imagery in the true-crime doc What Jennifer Did, from a few months ago. The newest example of this is found in Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam, a just-released Netflix docuseries that dives into the shady dealings of music industry impresario Lou Pearlman.

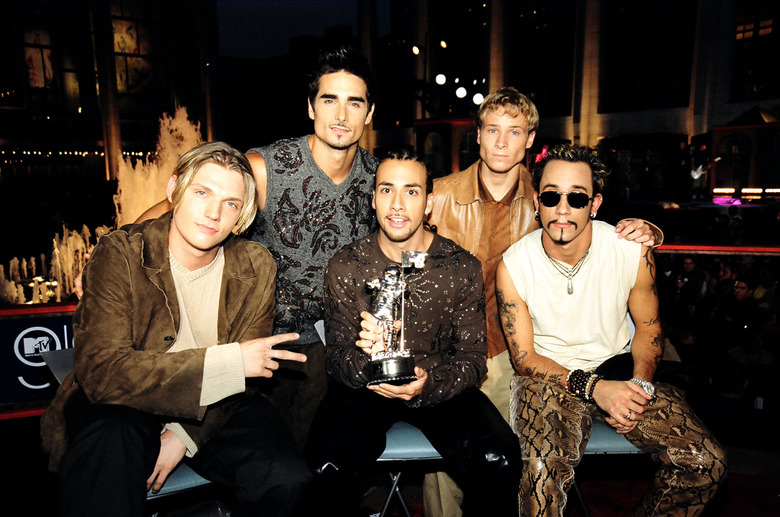

Pearlman, who died in 2016, was the pop music kingmaker behind groups like NSYNC and the Backstreet Boys.

"In addition to sharing never-before-seen home videos of your favorite baby-faced boy bands' early days," Netflix explains about Dirty Pop, "the three-part limited series pulls back the curtain on the glitz and glam surrounding the man responsible for launching so many careers and reveals the crooked and complex financial scheme he used to build the foundation of his unstable empire."

I want to focus on that mention of "videos" for just a moment.

Less than five minutes into Dirty Pop's first episode, we're shown what's clearly archival footage of Pearlman seated at a desk. A gold record is visible over his shoulder. He introduces himself to the camera — and then we stop hearing his voice, even though his lips are still moving. "This is real footage of Lou Pearlman," reads text that materializes on the screen.

Uh, ok, great? I kind of assumed it was.

"This footage," the wording continues, "has been digitally altered to generate his voice and synchronize his lips."

Pearlman's voice is now audible again — that is, the AI-generated voice is audible, matched with the footage of him we see onscreen. "I'm having an incredible life as an entrepreneur in the aviation and entertainment industries," Pearlman's AI voice says. "And I've made a little money too."

The screen then goes black, and new text materializes. Those words that Pearlman just spoke, we're told, were actually written by him in his book Bands, Brands, & Billions.

Some of you will probably roll your eyes at this ("What's the big deal? They disclosed that it's AI. And they used his own words that he actually wrote"), but this nevertheless feels like slippery-slope territory for me.

My discomfort here is not with the potential of the documentary tricking the audience. How could it do so, when the explanation of what's going on was clearly given up-front? Rather, it feels to me like any manipulation of the historical record — especially within the context of a fact-based documentary — sets a troublesome precedent. You want to use words that the guy wrote in a book? Show a picture of those words on the page. You want to use footage of the guy? Use footage of the guy.

Look closely at the first few syllables of the word "documentary." When you set out to create one, you're supposed to be documenting facts and content. Not manipulating them, even if that manipulation is in service of the truth. Let's not accelerate people's skepticism about whether seeing is believing anymore, even though we're clearly heading in that direction.