Chinese Rover Found Hidden Structures Beneath The Moon's Surface

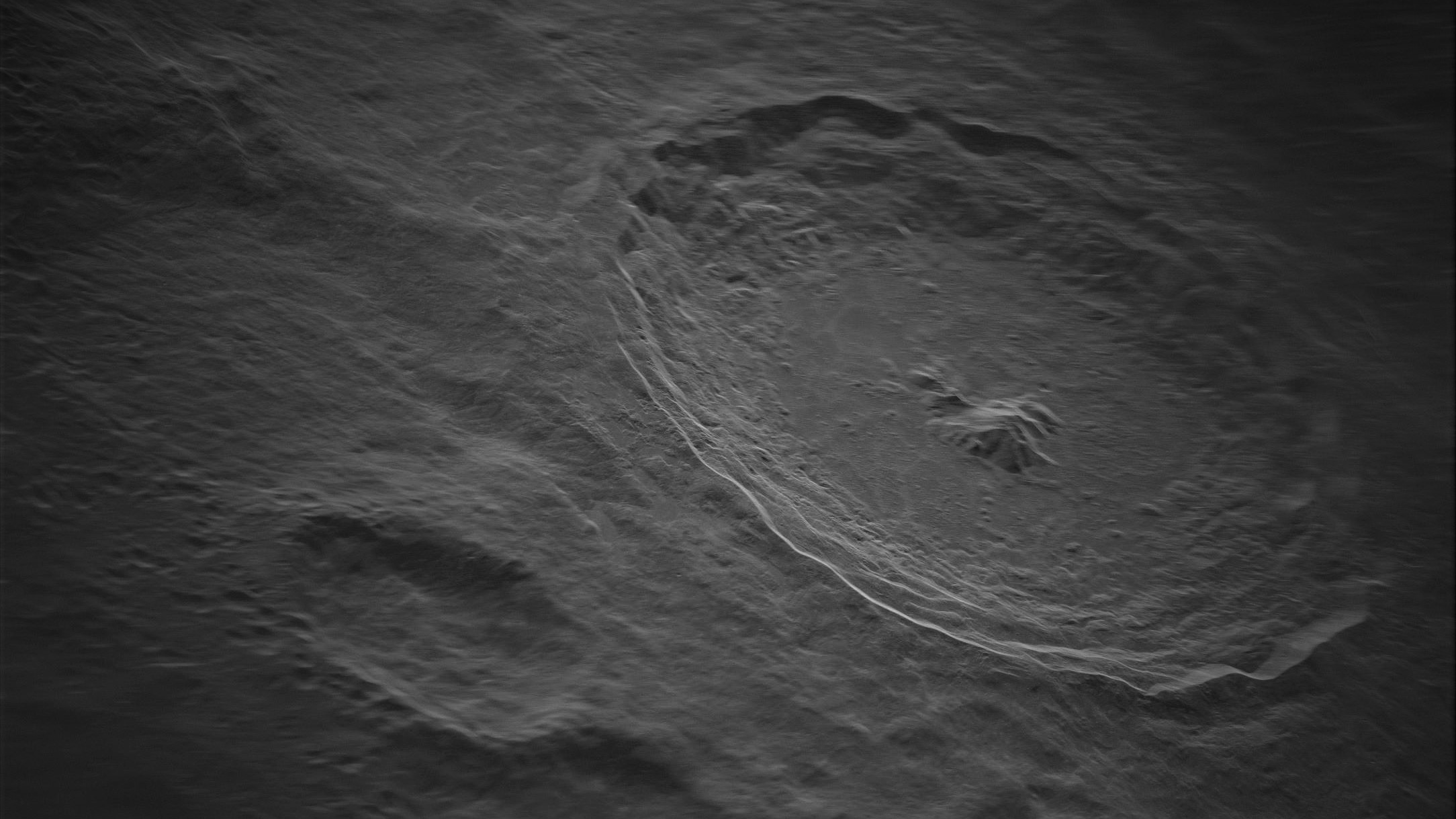

In 2020, researchers used recordings from the Yutu-2 LPR recorder to map out the first 130 feet below the moon's surface. Scientists have now mapped out the first 1,000 feet, uncovering several hidden structures beneath the moon's surface.

These layers of structures are believed to be volcanic rock, left behind after lava released by meteor and asteroid impacts cooled. The researchers shared their findings in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. The report reveals billions of years of previously unknown lunar history.

These lunar surface maps were made possible thanks to the Lunar Penetrating Radar (LPR) situated on China's Chang'e-4 rover, which became the first spacecraft to successfully land on the moon's far side in 2019. Now, using LPR, Chang'e-4 has allowed researchers the opportunity to look deeper into the moon than ever before.

The new data captured by LPR suggests that the first 130 feet of the moon's subsurface is comprised of multiple layers of dust, soil, and broken rocks. From there, we see layers of volcanic rock, first thin and then much thicker structures as we move deeper into the moon's subsurface. The belief here is that the thinner, newer layers showcase that the lava flow was much thinner during more recent eruptions.

This discovery seems on par with the ongoing theories that most volcanic activity on the moon ceased around a billion years ago, though some evidence suggests eruptions as recent as 100 million years ago. Because the eruptions stopped, though, the moon is mostly considered "geologically dead," so having a map of the moon's subsurface could help back that up.

Ultimately, discovering these hidden structures beneath the moon's surface is exciting because there's so much we don't know about our planet's lunar satellite. But Chang'e-4 isn't done with the moon just yet. We expect to see more discoveries from the Chinese rover as it continues to explore and dissect our lunar satellite, and it's likely we'll learn more once Artemis III lands on the moon later this decade.