Astronomers Discovered A Black Hole So Big It's Almost Unbelievable

2.7 billion light years away, in a galaxy cluster known as Abell 1201, an ultramassive black hole lurks, measuring upwards of 32.7 billion times the mass of our Sun. This new measurement exceeds astronomers' previous estimates by at least 7 billion solar masses. It's one of the biggest black holes astronomers have ever detected and cuts close to how large we believe they can be.

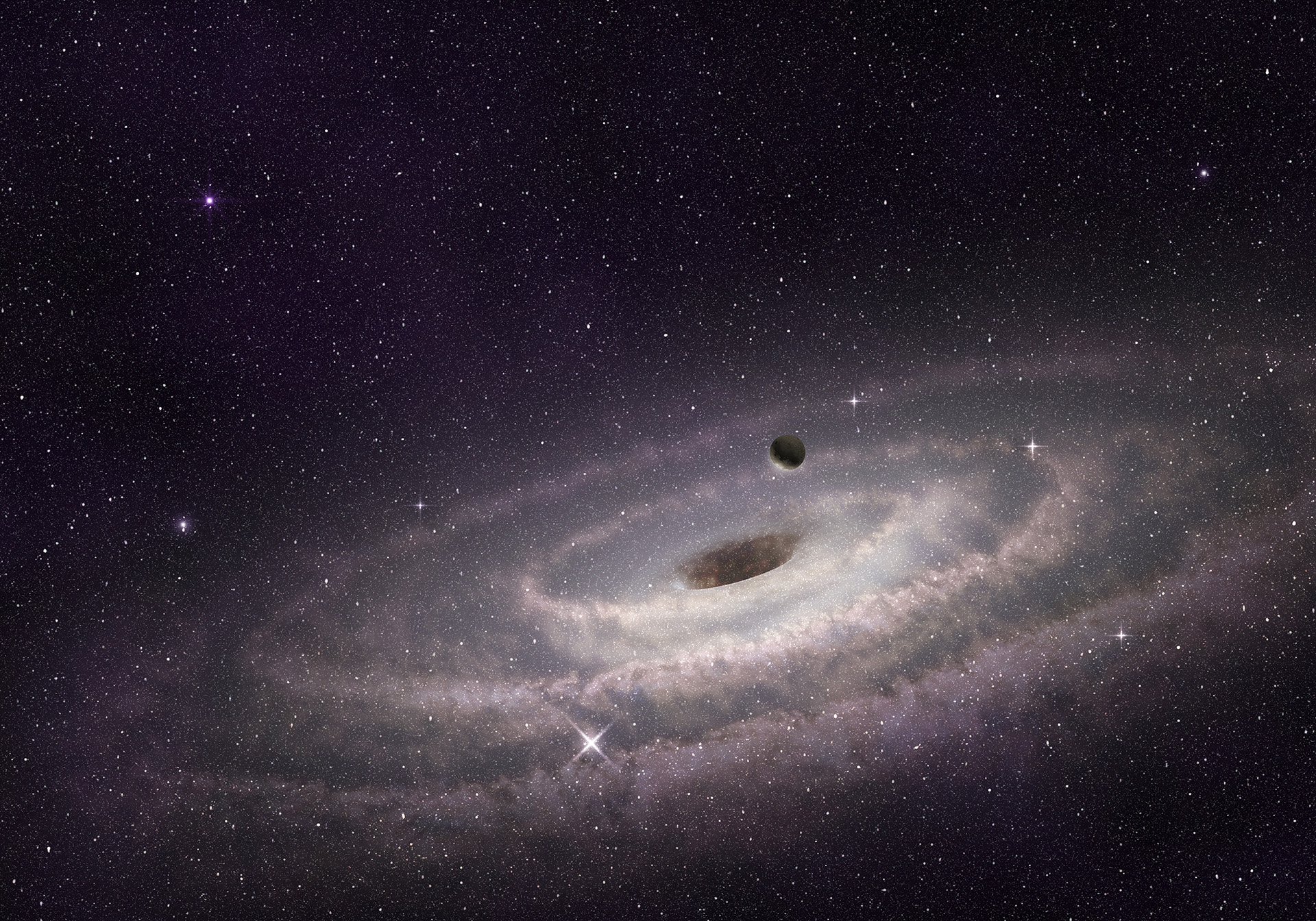

Our universe is filled with black holes, including the supermassive black holes found in the center of galaxies throughout all the regions of space around us. Many of these are inactive, not excreting material that causes them to light up, making them easier to detect. Others are rogue black holes, roaming through space however they please. Others still are ultramassive black holes.

These black holes are much bigger than supermassive black holes like those found at the center of galaxies. And, because they're so massive – and contain so much mass – they should theoretically be easier to find. However, as I noted above, it all depends on how active the black hole is and how much heat it emits. That's because, by default, ultramassive black holes (and black holes overall) don't emit light.

That makes them exceptionally difficult to spot in the blackness of space, where light is a huge factor in how we search for things. One way that astronomers search for black holes is called gravitational lensing. This technique sees astronomers observing how light travels through a region of space. In the case of this ultramassive black hole, the light curves exponentially around it.

That's because when light approaches a massive object in space, it lenses around it, stretching and creating a magnified effect that distorts images in the background. This is also useful for finding galaxies that are too far away for us to observe without immense magnification. A group of astronomers first noticed light bending around this ultramassive black hole at the center of Abell 1201 in 2003.

However, it wasn't until 2017, when astronomers discovered a second smear, that they began to look more in-depth at the discovery. More recently, they ran simulations, finding that for the light to bend around a black hole this way, it would have to measure roughly the same mass as 30 billion Suns, making it big enough to be an ultramassive black hole.

The researchers involved in the detection reported it in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The hope is that gravitational lensing will allow us to peer even deeper into the universe and discover more ultramassive black holes like this one, which has already made its way into the top 10 biggest black holes we've ever seen detected.