Space Can Make Your Blood Flow Backwards

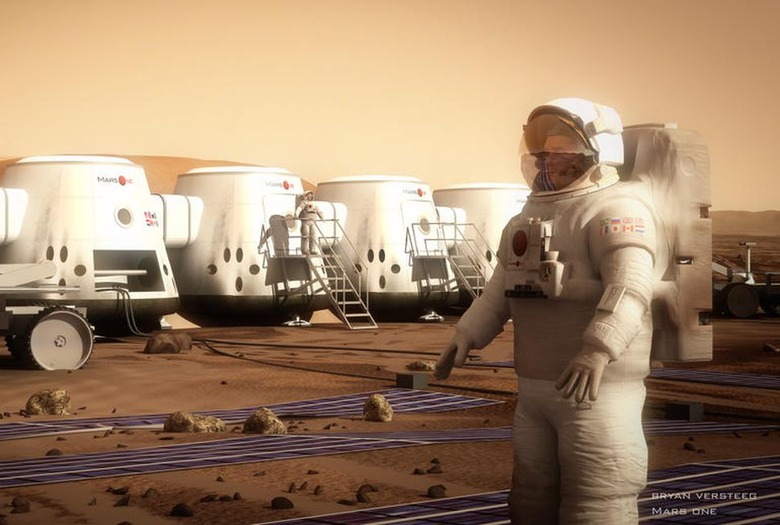

NASA wants to send humans to Mars. Much of the technology to make such a mission a reality is already in place, and other vital systems could be developed in time for a crewed trip to the Red Planet in the 2030s. It's exciting, but the journey will be long, and one serious question remains unanswered: How will human bodies react?

Scientists have been studying the effects of space travel on our bodies for some time. We know the short-term impacts of weightlessness are minor, but the long-term changes aren't nearly as well understood. A new study reveals that we have a lot to learn and that spending a significant amount of time in space can have bizarre effects on blood flow.

The paper, which was published in JAMA, examined the circulatory changes that took place in 11 different space travelers that spent time aboard the International Space Station. It found that while blood flow was perfectly normal when the scientists left Earth, dramatic changes had already begun by their 50th day in space.

In particular, circulation changes through the head and brain raised some serious concerns. In seven of the space travelers, blood flowing from the head down to the rest of the body showed signs of stagnation and, in some cases, even reversal.

On Earth, gravity aids in draining blood from the head and ensuring a steady flow. In space, that assistance just isn't there, and slow-moving or stagnant blood can cause clotting. In fact, two of the crew members were found to have clots or partial clots in their left internal jugular vein. Blood clotting is incredibly dangerous when it happens within the body, and if a clot were to form and then travel to the lungs it could create a pulmonary embolism, which is a potentially fatal condition that requires immediate treatment.

From the study:

By spending approximately two-thirds of the day upright and the remaining one-third of the day supine at night, humans experience fluid shifts daily. However, crew members on the International Space Station (ISS) are weightless and thus experience a sustained redistribution of fluids toward the head that is not subject to daily diurnal posture-induced change in hydrostatic pressure.

This is already a potentially serious problem for travelers to make their way to the ISS, but travel to Mars would be an even riskier proposition. Even by the most optimistic estimates of flight time to and from Mars, astronauts traveling to the Red Planet would be spending 400 or more days in space and floating weightlessly for nine-month stretches during both legs of the journey.

Artificial gravity systems could provide a solution, but the technology is still in its infancy and there's obviously no spacecraft that's been designed with these in mind. That may change in the future, but it's abundantly clear that a solution is needed before a crewed trip to Mars can even be realistically considered.