Microsoft Invents Glass That Stores Data

Like it or not, we'll always need solutions for storing data. Tech innovations such as fast data speeds like 5G and Wi-Fi 6 will let you download better quality shows and games than before, while the phone in your pocket can record 4K clips and take plenty of pictures, which usually require frequent backups. Then you have your operating system and apps, your work data, and you may even be in charge of managing the storage of your family's memories. Solid-state drives definitely help with all the backups and storage needs, and while they're cheaper than ever, they're also more expensive than traditional hard drives — and they won't last forever.

Microsoft is looking to fix some of the world's endless storage needs by using a brand new material for data: Nearly indestructible Quartz glass that can hold permanent copies of data.

It's called Project Silica internally, and Microsoft has been working on it for a while. The company explained in a blog post how it all works, and why it's something companies will want to pay attention to in the future.

Before you get too excited about getting your hands on a glass drive, or whatever these things end up being called, you should know the technology is in its infancy — and it doesn't work like you might expect.

Quartz copies can only be written once, with the help of femtosecond lasers, which are used in LASIK procedures. These lasers carve voxels, 3D representations of pixels, and each voxel is unique. Then, machine learning algorithms can read the different patterns and decode the data. A 2mm piece of Quartz can contain more than 100 layers of voxels, Microsoft says, without telling us how much data that would amount to.

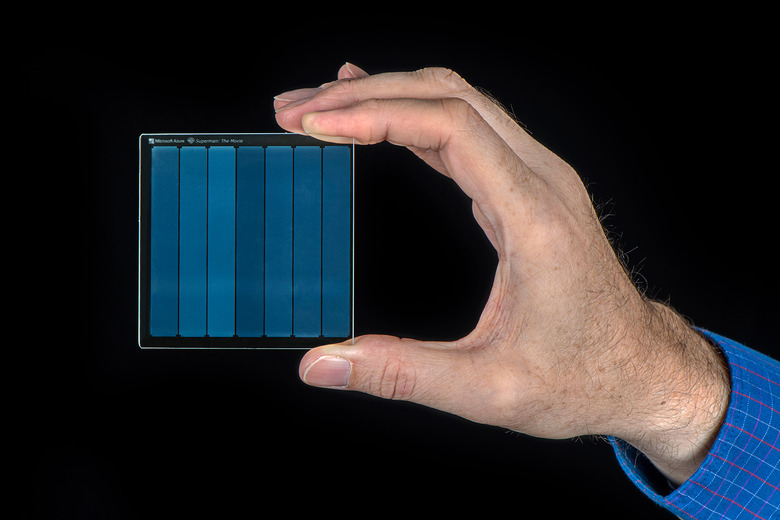

But the glass drive shown in these images suggests that storing a film like Warner Bros's Superman is possible on a rather tiny piece of glass — 75 by 75 by 2 mm:

This brings us to the kind of customers that will want (or need) to store their data this way. Movie studios, and any organization or company that needs to store large amounts of data and make sure that data can't be destroyed by the environment, or natural disasters, will want this sort of storage.

Microsoft boiled the glass, baked it in an oven, microwaved it, flooded it, and performed all sorts of tests only to discover that the voxels were still intact, and the data was still usable. This is also the kind of read-only data that companies like Warner Bros. might want to use for the cloud and streaming services of the future, as glass copies will always preserve the original quality of the film, as intended by the makers.

The lengthy report also details the pains studios go through to preserve their increasingly large collections by looking at how Warner Bros. does it:

The company has redundancy plans in place to handle multiple worst-case scenarios: an earthquake or hurricane that strikes one of the coasts, a fire where the suppression systems don't kick in or a climate control failure that allows moisture to build up and ruin film stock.

The goal is to have three archival copies of each asset stored in different locations around the world: two separate digitized copies, along with the original physical copy on whatever medium a film or television episode or animated cartoon was created.

Also interesting is the process by which Warner turns its digital-only content into physical copies:

Right now, for theatrical releases that are shot digitally, the company creates an archival third copy by converting it back to analog film. It splits the final footage into three color components —cyan, magenta and yellow — and transfers each onto black-and-white film negatives that won't fade like color film.

That process isn't just time-consuming and expensive, but it doesn't guarantee that the copies will be preserved forever, as the negatives need to be placed in tightly controlled storage facilities. Moreover, converting digital formats to film can't be environment-friendly, and the process might actually ruin the original quality of the digital version of the film. The following video explains Project Silica in detail, but Microsoft's full write up is also worth checking out: