Breakthrough Tech Could Double The Amount Of Energy Generated By Solar Cells

Solar power has always seemed on its surface to be the perfect solution to the world's reliance on fossil fuels. After all, sunlight is free and abundantly available. The problem has always been efficiency, since solar panels generate power far less efficiently than other options. In fact, it takes about 40 square meters of solar panels to generate enough energy to power just one American home for a day, based on average use.

Progress is slowly being made in labs around the world, though you might not know it by looking at the recent performance of solar stocks. But now, a breakthrough in the way solar energy is collected could double the amount of power generated by solar panels without dramatically increasing cost.

DON'T MISS: Revolutionary new laser system could detect bombs at airports in microseconds

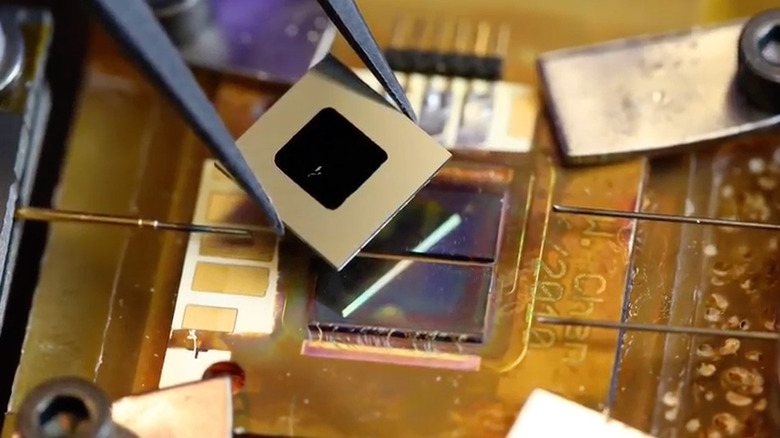

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology published a paper this week in the journal Nature Energy in which they describe how they built a working solar thermophotovoltaic device (STPV). Using this revolutionary new setup, the researchers think they can dramatically increase the amount of energy solar panels generate by harnessing some of the energy current panels waste.

A normal solar cell converts sunlight into energy and delivers it to a storage mechanism. Meanwhile, the heat energy created in the process simply dissipates and is wasted. Scientists have been working for years to find a way to harness some of that wasted heat, and now it appears as though the team at MIT is onto something.

The MIT researchers have added a new layer to a solar cell's structure that absorbs heat energy and converts it to light, which is then reflected off to another solar cell. The reflected light is also delivered to the second cell at the perfect wavelength for peak efficiency.

Of course, that's an oversimplification of the process. Here's a more detailed explanation from the team's abstract:

Solar thermophotovoltaic devices have the potential to enhance the performance of solar energy harvesting by converting broadband sunlight to narrow-band thermal radiation tuned for a photovoltaic cell. A direct comparison of the operation of a photovoltaic with and without a spectral converter is the most critical indicator of the promise of this technology.Here, we demonstrate enhanced device performance through the suppression of 80% of unconvertible photons by pairing a one-dimensional photonic crystal selective emitter with a tandem plasma–interference optical filter. We measured a solar-to-electrical conversion rate of 6.8%, exceeding the performance of the photovoltaic cell alone. The device operates more efficiently while reducing the heat generation rates in the photovoltaic cell by a factor of two at matching output power densities. We determined the theoretical limits, and discuss the implications of surpassing the Shockley–Queisser limit.Improving the performance of an unaltered photovoltaic cell provides an important framework for the design of high-efficiency solar energy converters.

Too much? Here's a slightly simpler explanation from MIT News:

The basic principle is simple: Instead of dissipating unusable solar energy as heat in the solar cell, all of the energy and heat is first absorbed by an intermediate component, to temperatures that would allow that component to emit thermal radiation. By tuning the materials and configuration of these added layers, it's possible to emit that radiation in the form of just the right wavelengths of light for the solar cell to capture. This improves the efficiency and reduces the heat generated in the solar cell.

"We believe that this new work is an exciting advancement in the field, as we have demonstrated, for the first time, an STPV device that has a higher solar-to-electrical conversion efficiency compared to that of the underlying PV cell," said MIT professor Evelyn Wang, one of four authors of the paper. Other researchers working on the project include David M. Bierman, Andrej Lenert, Walker R. Chan, Bikram Bhatia, Ivan Celanović and Marin Soljačić.

So far the new tech has only been demonstrated at a small scale in a lab environment, so the next step is to determine how STPV technology can be scaled it up economically.