The Brightest Light In The Sky Is No Longer A Star

The brightest lights in the sky no longer belong to stars after a new satellite was spotted in the night sky. The satellite is BlueWalker 3, and while it looks like a Tetris block, the satellite is more well known for being as bright as two of the brightest stars in the night sky.

The prototype satellite was spotted in the sky early Monday morning, October 2, and it peaked at close to the same brightness as two of the brightest stars in the sky, Achernar and Procryon. While this brightness isn't constant, BlueWalker 3's peak brightness being so high has raised other concerns about the overall light pollution that satellites like it could provide.

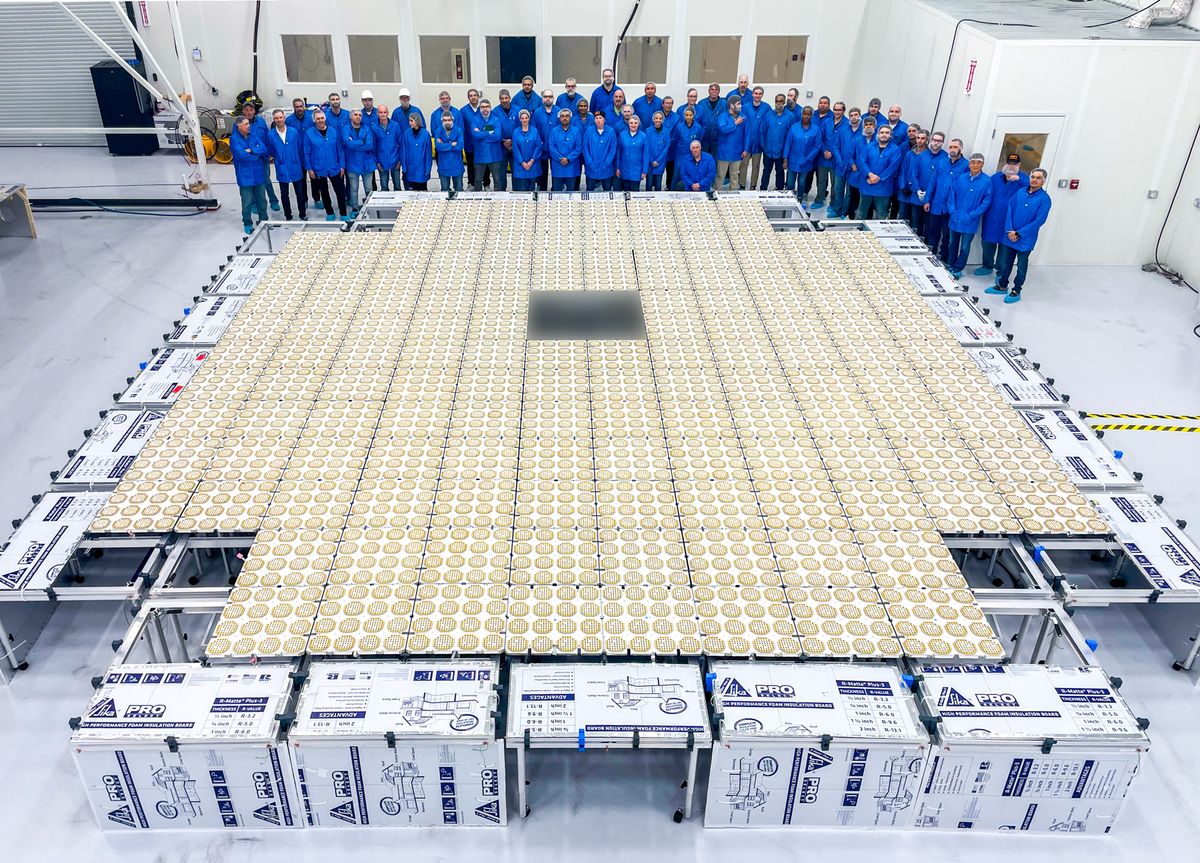

Unfolded, BlueWalker 3 is a 64-square-meter array that is visible in dark skies and urban skies. While the satellite might only be visible in urban skies when directly overhead, these large constellations pose a significant challenge to ground-based astronomy, blocking the potential light of planets and stars that astronomers might be trying to observe.

This isn't the first time we have seen concerns about the way the night sky is becoming lit up by large constellation satellites. We've even seen concerns about how these large groupings of satellites affect orbiting telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope. As such, seeing a satellite that can appear as bright as the brightest stars in the sky is very concerning.

But the concerns don't end there. Sure, BlueWalker 3 is very bright, but the radio frequency used for the prototype satellite and the upcoming predecessors is also very close to the frequencies used for radio astronomy, which means they could interfere with ground-based observations in more than one way.

Developed by AST SpaceMobile, the new satellite launched in September of last year. Now that it's in orbit and fully unfolded, the satellite reflects sunlight off a massive area. It's also the closeness of the satellite to Earth – because of its low-earth orbit – that makes the brightness so concerning.

If it was placed in a further out, geostationary orbit, the satellite might not pose such a problem for skywatchers and astronomers using ground-based telescopes. This new study is just another barrel of fuel on the fire that will continue to see researchers standing up to "big light" as astronomers call for a cap on the number of low-altitude satellites that can be put into orbit at one time.

Without any kind of cap, we could one day have a sky so polluted with artificial light that we can't observe anything beyond it.