Scientists May Have Solved One Of The Biggest Mysteries Surrounding Migraines

Migraines are the absolute worst. Whenever I get one, I know I'm about to be knocked out for the day. After the aura passes, I know that a throbbing headache will follow, and I'll have to deal with remnants of that pain for at least a couple of days. Luckily, I don't get migraines that often, and I can't imagine what it must be like to get them regularly.

The good news is that we might be getting closer to new therapies to treat migraines and the headaches that follow. Researchers from the University of Rochester have figured out how an aura episode triggers a chain of events that ultimately leads to headaches. Previously, this was one of the biggest mysteries surrounding migraines.

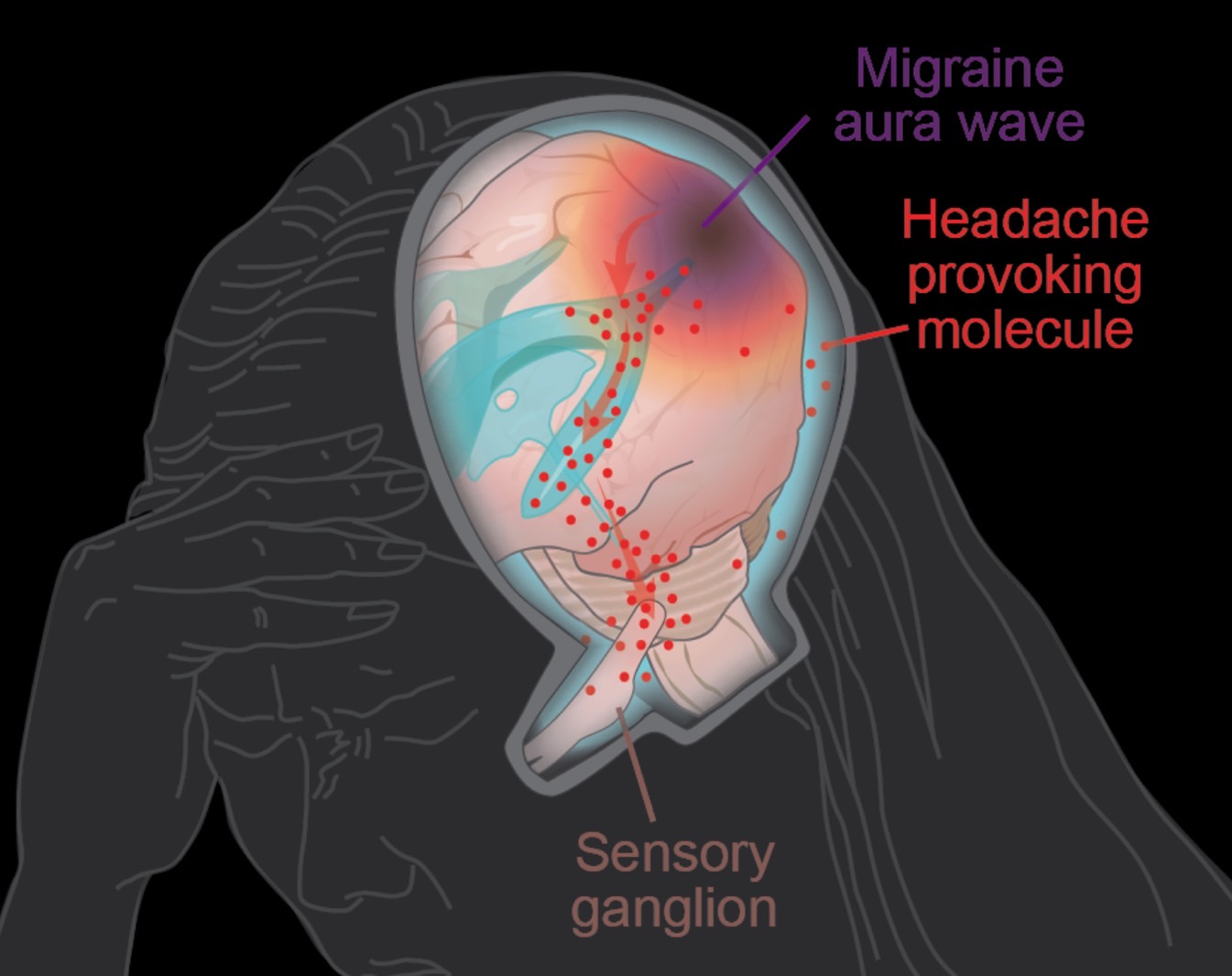

They've discovered that auras lead to movements in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounding the brain. In turn, this movement releases certain proteins, which can interact with nerves and lead to pain. These proteins may become targets of new therapies that reduce or even entirely prevent migraine headaches.

"In this study, we describe the interaction between the central and peripheral nervous system brought about by increased concentrations of proteins released in the brain during an episode of spreading depolarization, a phenomenon responsible for the aura associated with migraines," Maiken Nedergaard, co-director of the University of Rochester Center for Translational Neuromedicine and lead author of the new study, said in a statement. "These findings provide us with a host of new targets to suppress sensory nerve activation to prevent and treat migraines and strengthen existing therapies."

The migraine aura is a sensory disturbance that can include a variety of symptoms. You can expect flashes, blind spots, double vision, tingling sensation, or limb numbness. For me, it's typically blind spots. These symptoms last between five and 60 minutes before a headache, and that's how I know pain is imminent.

This new study indicates that about a quarter of migraines start with auras. Moreover, one out of 10 people experience migraines. That's quite a lot of people who could be helped by novel therapies targeting this newly discovered pain mechanism.

The auras happen after a cortical spreading depression or a depolarization of neurons following the diffusion of glutamate and potassium. This depolarization turns into a wave that radiates across the brain, impacting oxygen levels and blood flow. The visual symptoms appear because depolarization often occurs in the visual processing area of the cortex.

When auras occur, the brain itself can't sense pain. Instead, a communication process occurs between the brain and peripheral sensory nerves, as the scientists observed in the study.

In 2012, Nedergaard and her colleagues described the glymphatic system in the brain. This system uses the CSF to remove toxic proteins that can be present in the brain. For the new study, the scientists looked at how the CSF moves proteins and other substances during migraines.

The researchers were able to provide a different explanation for headaches in migraines. The most widely accepted theory says that nerve endings on the outer surface of the brain membranes are involved in headaches following auras. The new study challenges that with a new pathway for pain.

As depolarization occurs during an aura, neurons release all sorts of proteins in the CSF. Nedergaard & Co. showed that the fluid transports these proteins to the trigeminal ganglion at the base of the skull. This is a large bundle of nerves that gathers sensory information from the head and face.

More interestingly, the researchers found that the CSF flows directly into the trigeminal ganglion, thus challenging another theory. Until now, it was believed that this large nerve sat outside of the blood-brain barrier, meaning that it would not interact with the flow of chemicals in the brain.

The proteins released during the auras travel via the CSF to the trigeminal ganglion. The nerve endings are exposed to these proteins, and pain occurs. The researchers also figured out that protein released on one side of the brain would travel to the same side of the trigeminal ganglion's nerves. That explains why pain largely occurs on one side during migraines.

Nedergaard's team identified 12 ligand proteins that bind to the nerve receptors. The concentration of some of these nerves more than doubled after an aura. One of them is the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) protein, which is already the target of new drugs to prevent and treat migraines. These are called CGRP inhibitors.

As someone suffering from migraines occasionally, I can only hope pharmaceutical companies are paying attention to this breakthrough migraine discovery.

The full study is available in Science magazine.