Scientists Figured Out Why Some People Don't Lose Weight Even When They Work Out

If you're struggling to lose weight despite exercising regularly, you will be happy to hear there's a new study that might have solved the mystery.

It turns out that you might be missing a key metabolic component that prevents you from burning fat during workouts. Moreover, you might consume less oxygen while exercising. In turn, you risk gaining weight, which can lead to obesity and diabetes. The new study suggests there might be new ways to target obesity other than drugs that aim to reduce appetite.

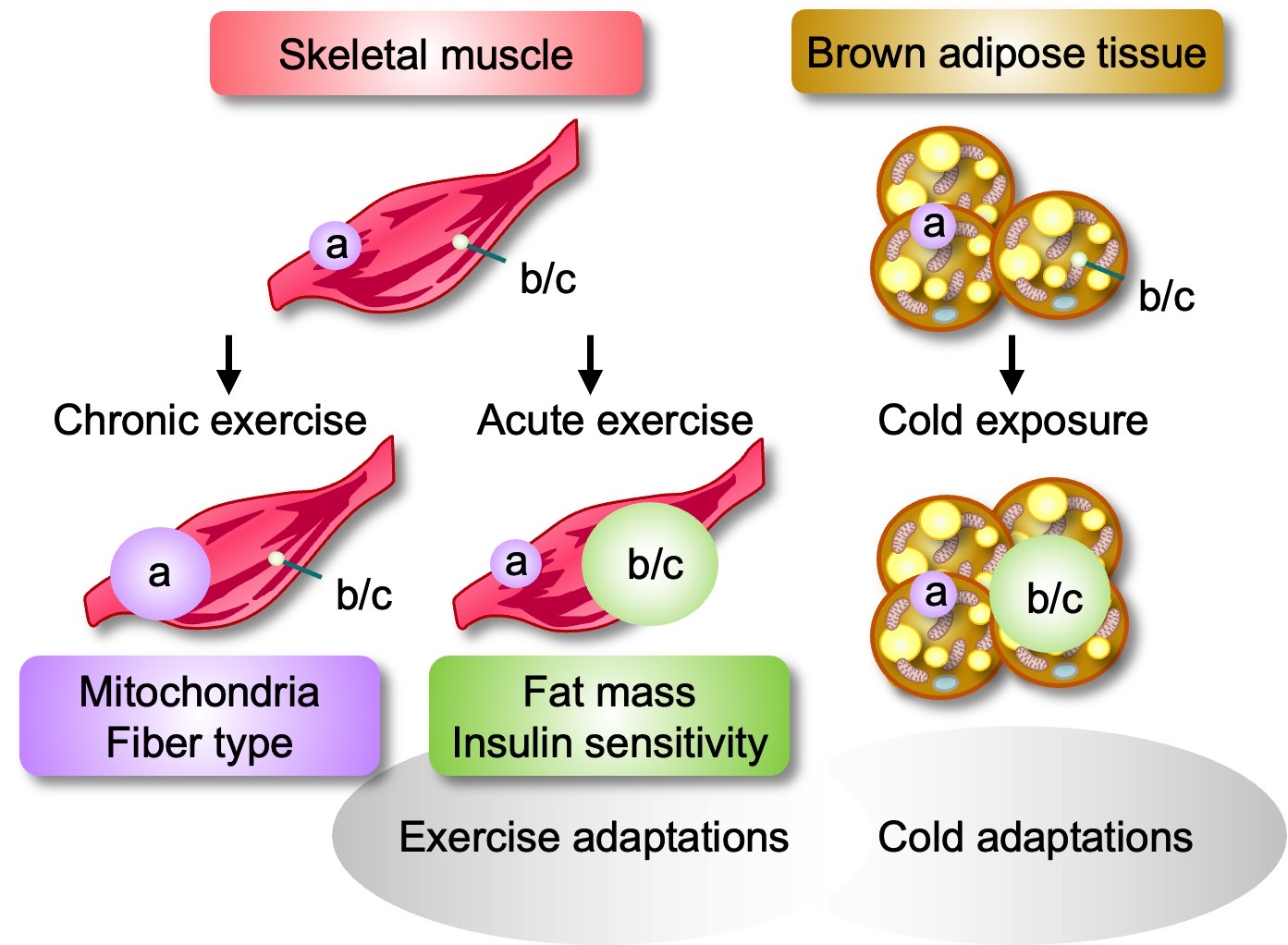

Researchers from Kobe University looked at a signal molecule called PGC-1⍺ ("a"), which is involved in burning fat while exercising.

The body produces multiple versions of the protein, including so-called "b" and "c" variants. These two have the same function as the "a" signal molecule, with a big difference. The "b" and "c" variants are produced in muscles more than 10 times more during exercise. Meanwhile, version "a" doesn't show a similar increase.

Kobe University endocrinologist Ogawa Wataru and his team hypothesized that molecules "b" and "c" are responsible for energy metabolism during workouts. That is, they'll help you burn fat while exercising.

For the experiment, they created mice that lacked the "b" and "c" signal molecules, operating only on the "a" variant. Then, they measured muscle growth, fat burning, and oxygen consumption during three phases: rest, short-term exercise, and long-term workouts.

Furthermore, they recruited human volunteers with and without type 2 diabetes for similar tests. People who are obese and those with type 2 diabetes might also have reduced levels of the signal molecule.

The researchers concluded that mice lacking "b" and "c" molecules were not able to adapt quickly to short-term activity. Therefore, they consumed less oxygen and burned less fat during and after workouts.

The scientists obtained similar conclusions when studying human volunteers. Both healthy subjects and those with type 2 diabetes consumed more oxygen and had less body fat the more "b" and "c" proteins they produced.

However, the study also discovered that long-term exercise might benefit subjects who only produce the "a" protein. The mic who exercised regularly developed more muscle after six weeks of training, regardless of whether they could make the "b" and "c" proteins.

Interestingly, the researchers found another important functionality of the PGC-1⍺ protein and its variants. It can impact the way subjects react to cold.

This time, they looked at PGC-1⍺ changes in the fat tissue. When exposed to cold, the mice produced more "b" and "c" proteins that helped them burn fat to keep warm. The animals that could not make "b" and "c" proteins had their body temperatures drop significantly when exposed to cold.

This finding seems to indicate that the "b" and "c" versions of the signal molecule might trigger metabolic reactions in response to all sorts of short-term stimuli, not just workouts.

The main takeaway concerns the ability of subjects to burn fat during and after exercise.

"Recently, anti-obesity drugs that suppress appetite have been developed and are increasingly prescribed in many countries around the world," Ogawa and his team said in a statement.

"However, there are no drugs that treat obesity by increasing energy expenditure. If a substance that increases the 'b' and 'c' versions can be found, this could lead to the development of drugs that enhance energy expenditure during exercise or even without exercise. Such drugs could potentially treat obesity independently of dietary restrictions."

The full study is available in Molecular Metabolism. The researchers are now studying how the "b" and "c" proteins increase in muscles during exercise.