Scientists Found A Massive 'Dragon Man' Head That May Belong To A New Species

Scientists studying human evolution have delivered two breakthrough discoveries in a matter of days. First, it was a team in Israel that analyzed fossilized bone fragments from a skull belonging to what turned out to be a new species of human. Baptized Nesher Ramla Homo, the species roamed the region around modern-day Israel about 130,000 years ago. It's believed to have cohabitated with Homo sapiens, interbreeding and exchanging information about technology and culture. Nesher Ramla might turn out to be the missing link, a Neanderthal precursor that researchers were looking for.

Separately, scientists from China have studied a massive human head fossil that they believe belongs to an entirely different species, currently named Homo longi or "Dragon man." Other experts disagree with their Chinese fellows, and they say that it might be premature to designate a new humanoid species.

Found in Harbin, the skull above might also help rewrite human evolution because the Homo longi might have been a group more closely related to modern Homo sapiens than the Neanderthals.

The fossil was first discovered in 1933 by Chinese workers building a bridge over the Songhua River during the Japanese occupation. To prevent it from falling into the hands of their occupiers, the workers wrapped the skull and hid it in a well, The Guardian reports. It resurfaced only in 2018 when the man who hid the skull told his grandson about it on his death bed.

Researchers at the Hebei Geo University in China determined that the Harbin skull was at least 146,000 years old. The skull features a unique combination of primitive and modern features. The face resembles Homo sapiens more closely than the Nesher Ramla Homo, the report notes.

The skull measures 23cm long and more than 15cm wide. It's significantly larger than a modern human head and has ample room for a modern human brain.

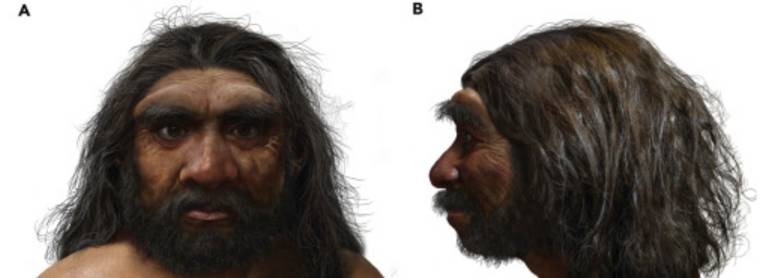

Reconstruction of the Homo longi skull: Anterior view (A) and lateral view, left side (B).

The skull features a thick brow ridge and large square eye sockets. But it's also delicate despite its size. It belonged to a male about 50 years old who would have had a similarly impressive physique. A wide nose would allow the passage of vast volumes of air, which would support a high-energy lifestyle. The man's overall size would have helped him withstand the very cold winters in the region.

"Homo longi is heavily built, very robust," Hebei paleoanthropologist Prof Xijun Ni said. "It is hard to estimate the height, but the massive head should match a height higher than the average of modern humans."

The researchers compared the Harbin skull to 95 others with the help of computer software and compiled the most likely family tree. That's how they discovered that the Harbin skull and a few others from China formed a branch that's closer to modern humans than Neanderthals.

While Chinese researchers believe the Harbin skull is distinct enough to make it a new humanoid species, others disagree. One of them is Prof Chris Stringer, research leader at the Natural History Museum in London, who worked on the "Dragon man" project. He said it was one of the most important findings of the past 50 years, "a wonderfully preserved fossil." But he believes it is similar to another fossil found in Dali county in China. "I prefer to call it Homo daliensis, but it's not a big deal," he said. "The important thing is the third lineage of later humans that are separate from Neanderthals and separate from Homo sapiens."

There's a possibility the human belongs to the Denisovan, a group of extinct humans, but more research is required to prove the connection.

Regardless of the name or species, other researchers are excited by the finding, per The Guardian. "The beautifully preserved Chinese Harbin archaic human skull adds even more evidence that human evolution was not a simple evolutionary tree but a dense intertwined bush," said UCL professor of earth system science Mark Maslin. "We now know that there were as many as 10 different species of hominins at the same time as our own species emerged." Despite that, it's the homo sapiens that ultimately came out as the dominant human species.

Data from the Harbin skull research was published in The Innovation in three separate papers: Here, here, and here.