Researchers Think They Finally Found The Key To Stopping The Coronavirus

- Several drugs already work as coronavirus therapies, but there's still no "miracle cure" that can prevent complications and reduce deaths significantly.

- Some researchers think they've figured out a different way to approach COVID-19 treatment, looking at the illness as a vascular disease first.

- There are already ideas on what new types of drugs might be used to combat the disease, and a limited exploratory trial has offered promising results.

We are now entering our ninth month of the novel coronavirus pandemic and the infection may seem scarier than ever, given how many people keep catching COVID-19 every single day. But we've learned so much about the virus during this time that we actually have a chance of fighting it. If it weren't for all the people who ignore safety measures and for the anti-maskers who refuse to listen to experts, we would already have reduced the spread and prevented countless deaths. The good news is that physicians who have been treating the illness for the better part of a year already have an idea of what works on patients, and plenty of drugs are in advanced stages of trials, including vaccine candidates that might prevent infections in the near future.

Each new week brings us more details about the virus that can help us fight it better than before, and some researchers think they have now figured out the real key to stopping the novel coronavirus pandemic. COVID-19 should be viewed not as a respiratory disease first, some researchers say, but as a vascular illness. The same study says it's not the much-talked-about cytokine storm that leads to complications and death, but a different kind of "storm" that takes place inside the body before the immune system goes into overdrive.

The Summit supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Lab in Tennessee analyzed more than 40,000 genes from 17,000 genetic samples to better understand COVID-19, writes Thomas Smith on Medium. The computer is the second-fastest in the world, yet it still needed more than a week to crunch 2.5 billion genetic combinations. Once the data was processed, Dr. Daniel Jacobson and his colleagues formulated a new hypothesis they think explains everything that can happen after the coronavirus infects your body. They also think they know how to treat it using drugs that are already available.

That's the bradykinin hypothesis, which refers to a compound that's affected directly by the virus, and which could lead to a "bradykinin storm" that can cause serious problems and lead to death.

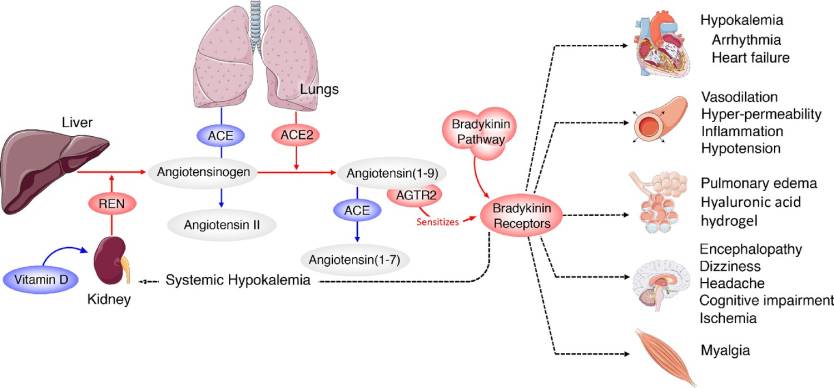

The data from the Summit computer shows that the novel coronavirus doesn't only infect cells that have ACE2 receptors, which bind to the pathogen's spike protein. Instead, it tricks the body into upregulating ACE2 receptors in places where you wouldn't normally find them, including the lungs.

That's where the Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) system comes into play. RAS controls the levels of bradykinin in the body, which has a direct effect on blood pressure. But the virus can interact with the RAS system, which then increases the number of bradykinin receptors. At the same time, the body stops breaking down the substance, and that leads to a so-called bradykinin storm.

As bradykinin accumulates, the effects start showing up. The compound increases vascular permeability, which means water from the blood can leak through the vessels and into neighboring tissue. When this happens in the lungs, liquid starts to build up and cells from the immune system also end up mixed in, thus contributing to inflammation.

From the study: "Systemic-level effects of critically imbalanced RAS and bradykinin pathways."

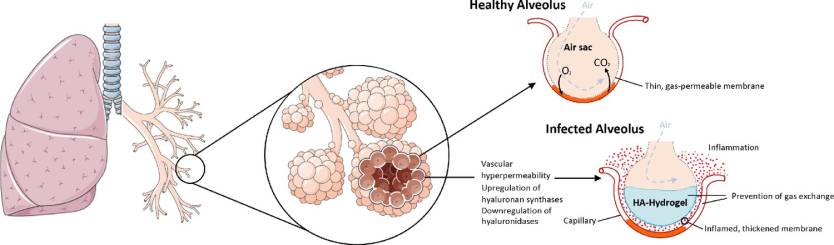

Jacobson and his team think COVID-19 might have another effect that further complicates things. The virus increases the production of hyaluronic acid (HLA) that can absorb plenty of fluid. When HLA interacts with the fluid in the lungs, the end result is a hydrogel that makes it even more difficult to breathe. At that point, it's likely that not even ventilators will be able to help. "It reaches a point where regardless of how much oxygen you pump in, it doesn't matter because the alveoli in the lungs are filled with this hydrogel," Jacobson says. "The lungs become like a water balloon."

The researchers think that the RAS-bradykinin imbalance can explain heart symptoms that appear with COVID-19, including arrhythmias and low blood pressure. Moreover, high doses of bradykinin could alter the protection offered by the blood-brain barrier, allowing some toxins to make their way to the brain. This could explain some of the neurological symptoms that appear in some COVID-19 cases. The dermatologic phenomenon described as COVID toe may also be attributed to the compound's ability to increase vascular permeability. The substance could have an effect on the thyroid gland as well, the researchers say, which could explain thyroid symptoms.

ACE inhibitors are a class of heart disease drugs that can lower blood pressure, and they have a similar effect on the RAS system as the novel coronavirus, which includes the increase of bradykinin levels. Therefore, COVID-19 can mimic the side effects associated with ACE inhibitor treatment in heart disease, including dry cough and fatigue, in addition to lowering blood pressure. The bradykinin effect could also increase blood potassium levels. ACE inhibitors are associated with the sudden loss of taste and smell as well, though, in the case of COVID-19, it's the virus infecting certain cells in the nose that explain the symptom.

The researchers also think that that the bradykinin hypothesis can explain why men are more at risk than women in COVID-19, as some RAS-related aspects are linked to sex thanks to proteins that are located on the X chromosome.

From the study: "The upregulation of hyaluronan synthases and downregulation of hyaluronidases combined with the BK-induced hyperpermeability of the lung microvasculature leads to the formation of a HA-hydrogel that inhibits gas exchange in the alveoli of COVID-19 patients."

The researchers believe that the bradykinin problem has a solution, and some drugs that are already FDA-approved might be helpful. The list includes danazol, stanozolol, and ecallantide, which could reduce the production of bradykinin. Icatibant can reduce bradykinin signaling. Jacobson and his team also say that Vitamin D might be helpful in COVID-19 management since it's involved in the RAS system and could reduce a different compound. These drugs might prevent bradykinin storms. Then, hymecromone is a different drug that could reduce HAL levels, which could reduce lung complications. Finally, a different drug called timbetasin could mimic the mechanism that protects women.

It's important to note this is just speculation based on the findings. More research is required on the topic, and it certainly seems like a hypothesis that's worth investigating. These drugs would need to be tested in clinical trials, as the researchers indicate.

A team of Dutch scientists seems to agree that the virus hinders bradykinin regulation, and this process has devastating side-effects in some patients. As The Scientist reported a few days ago, studies are already in place to look at the potential efficacy of drugs that can target the kinin system, including icatibant and a monoclonal antibody called lanadelumab. A small exploratory study showed that hypoxic patients who took icatibant soon after hospitalization improved in oxygenation and did not require supplemental oxygen therapy compared to a control group. This was not a randomized study, and some of the patients who got the drug still needed additional oxygen.

The full study from the Jacobson team is available in peer-reviewed form at this link, and could benefit from additional scrutiny and research from experts in the field.