Cancer Risk Drops As We Get Older, And This May Be Why

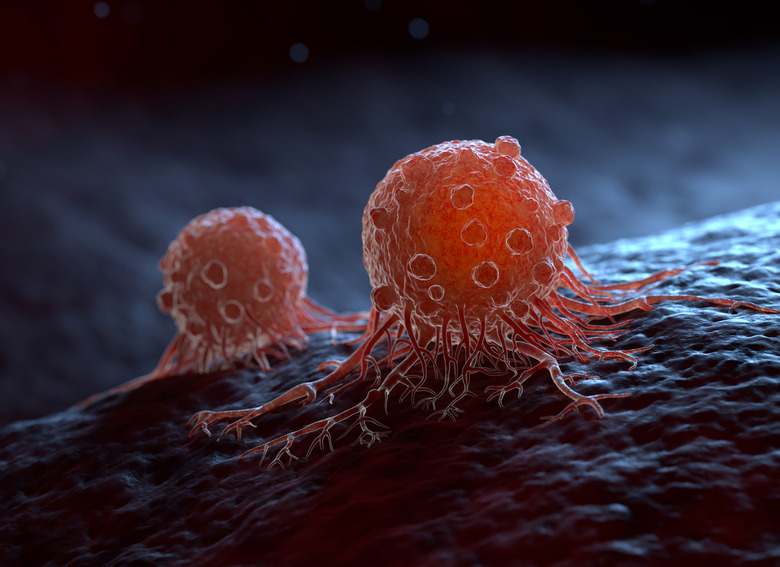

Cancer risk is a numbers game. It rises steadily as we age, with our 60s and 70s seeing the highest risk. Decades of accumulating genetic mutations create a fertile ground for cancer to develop. But here's the twist: after 80, the risk starts to decline. Scientists have long wondered why—and a new study offers some compelling clues.

An international research team investigated lung cancer in mice, focusing on alveolar type 2 (AT2) stem cells. These cells are crucial for lung repair and regeneration. However, they are also where many lung cancers originate. The researchers discovered a key protein, NUPR1, which behaves differently in older cells.

In aging mice, NUPR1 levels were elevated, causing cells to mimic an iron deficiency even though they actually had more iron. This "functional" iron shortage curtailed the cells' ability to regenerate, slowing not just healthy cell growth but also cancerous tumors. Interestingly, human cells displayed the same pattern.

When researchers artificially lowered NUPR1 or increased available iron, the cells regained their ability to grow. This could open doors to new treatment possibilities, particularly for older adults. For instance, therapies targeting iron metabolism could enhance lung function in patients with long-term damage, such as from COVID-19.

Beyond treatments, the study underscores the importance of prevention. Early-life exposures to carcinogens, like smoking or excessive sun tanning, appear to carry even greater cancer risks than once believed as we age. Minimizing these risks early on could significantly lower cancer rates in later life.

Scientists continue to learn more about the best ways to diagnose cancer. Understanding why cancer risk drops as we age is going to go a long way to helping us understand runaway cell growth and how it relates to cancerous tumors, too.

This study not only sheds light on the complex biology of aging and cancer but also hints at personalized treatment strategies. With age-tailored therapies, we can better address the nuances of cancer at every stage of life. The findings are published in the journal Nature.