Opening Schools Back Up Could Lead To A Massive Spike In New Coronavirus Cases

- A new study finds that children above the age of 10 can transmit the coronavirus just as easily as adults.

- The study is timely given the ongoing debate as to whether or not schools should reopen this fall.

- Some schools will implement a hybrid model that will divide the week into classroom learning and online instruction.

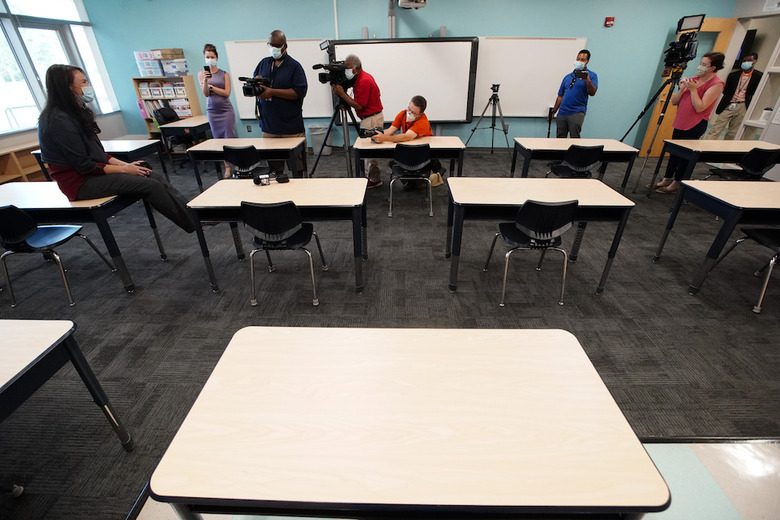

With the coronavirus pandemic still ongoing, there's currently a contentious debate as to how schools in the U.S. should re-open this coming fall, if at all. While some cities are planning to implement a hybrid system that would see kids go to school for 3 days a week and engage in online learning for the rest of the week, other cities still aren't sure how they plan to proceed. Some states like Florida, meanwhile, will be requiring schools to reopen next month.

Per usual, the issue of school re-openings has morphed into a political debate. This is an unfortunate development as science and health considerations have seemingly taken a backseat to political talking points.

One aspect of the debate worth covering in detail centers on the ability of kids to spread the coronavirus to adults. While children are far less likely to experience severe coronavirus symptoms, if any at all, the argument against school re-opening is that children will subsequently spread the virus amongst themselves and, by extension, to their parents and the community at large.

Bolstering this point of view is a new study from South Korea which found that children and young adults between the ages of 10 and 19 can spread the coronavirus just as easily as adults. Incidentally, the study found that kids below the age of 10 are far less likely to spread the virus.

Based on the above, there's a concern that school re-openings in August and September will inevitably lead to a massive spike in new coronavirus infections. And given that we're already seeing a rapid increase in new coronavirus cases while school currently isn't in session, the fear of a new coronavirus spike is arguably well-grounded.

As to the aforementioned study, The New York Times reports:

Several studies from Europe and Asia have suggested that young children are less likely to get infected and to spread the virus. But most of those studies were small and flawed, said Dr. Ashish Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute.

The new study "is very carefully done, it's systematic and looks at a very large population," Dr. Jha said. "It's one of the best studies we've had to date on this issue."

All the while, the debate surrounding school re-openings is only becoming more heated. This past Friday, for instance, Missouri Governor Mike Parson generated a bit of controversy when he conceded that kids will contract the coronavirus but argued that the impact will be negligible.

"And if they do get Covid-19, and they will when they go to school, they're not going to the hospitals," Parsons explained. "They're not going to have to sit in doctor's offices. They're going to go home, and they're going to get over it."

Of course, in light of the South Korean study above, children going home and spreading it to their parents is exactly the concern at hand. Further, many teachers are beyond concerned about the likelihood of contracting the virus themselves. In fact, teacher unions in Florida recently sued Governor Ron DeSantis over his mandate requiring schools to reopen next month.