Some People Might Already Be Immune To Coronavirus Thanks To The Common Cold

- Coronavirus immunity is the topic du jour, as health officials are looking to determine what sort of protection against reinfections the immune system has.

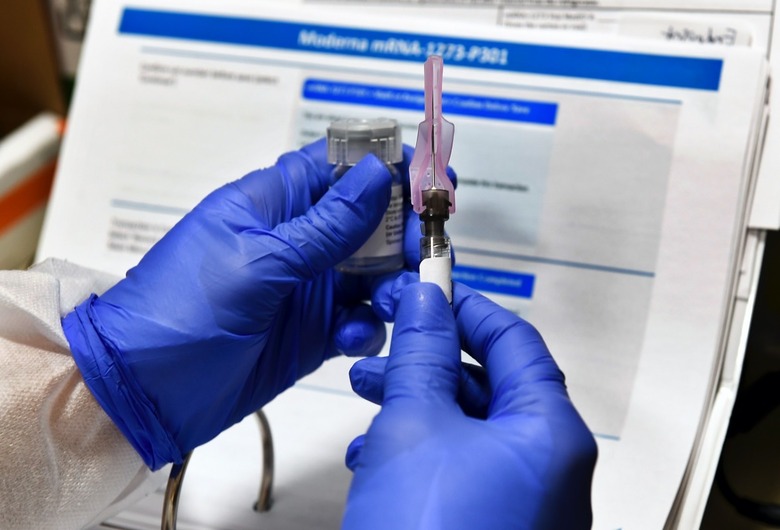

- Vaccines and other drugs could boost COVID-19 protection, but it's unclear how long-lasting the acquired immunity would be.

- A new study seems to echo findings from similar research, saying that a previous encounter with a human coronavirus that causes the common cold may induce an immune response that could offer protection against infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Long-lasting immunity to the novel coronavirus — that's the endgame. That's our way out of this pandemic. The best type of protection would come from the vaccines. These drugs would generate an immune response similar to what you'd develop while fighting COVID-19, and the immune system would be prepared to deal with the actual pathogen upon contact. The alternative is surviving COVID-19 without going through a severe, life-threatening case. Vaccines and other drugs could help with both these options, but we don't have any drugs yet.

Also, we have no idea how long immunity lasts. Available data suggests coronavirus immunity can't be longer than 12 months, given other human coronaviruses act. Recent studies have shown that antibodies can disappear after three months, but immunity doesn't go away. T cells that can remember the encounter with the virus would spring into action upon reinfection and kill the virus. But how long would those last?

Sadly, nobody can answer the COVID-19 immunity question right now. A new study says that some people may already be immune to the illness, though, and it's all thanks to the common cold.

Of the seven coronaviruses that can infect humans, four cause common colds. The other three can lead to serious complications and even death. SARS and MERS offered previews of what SARS-CoV-2 would do.

Researchers from Duke-NUS Medical School, the National University of Singapore, published a study in Nature that says that memory T cells created by previous encounters with other coronaviruses may be enough to create an immune response against COVID-19. The team tested COVID-19 survivors for T cells and discovered these types of white blood cells in all of them. Furthermore, the team found that patients who recovered from SARS 17 years ago still had SARS-specific T cells which could provide immunity against the novel coronavirus.

More interestingly, the researchers also tested people who have not been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in any way, finding they had T cells that could fight the virus.

"Our team also tested uninfected healthy individuals and found SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in more than 50 percent of them. This could be due to cross-reactive immunity obtained from exposure to other coronaviruses, such as those causing the common cold, or presently unknown animal coronaviruses. It is important to understand if this could explain why some individuals are able to better control the infection," Professor Antonio Bertoletti said.

The researchers are looking at other COVID-19 survivors to see how long the T cells persist in the body. What's interesting to note is that some of the vaccine candidates out there induce a double defense immune reaction that includes neutralizing antibodies and T cells. Even if you're somehow immune to COVID-19 due to a previous encounter with a different coronavirus, there's no way to tell unless you get your T cells sampled and tested. Also, this is the point where I'll tell you that more research is required on the matter, and we're anxious to see the results.

However, the Duke-NUS study is the third paper claiming that coronaviruses responsible for the common cold might induce some sort of immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Back in mid-May, we covered two similar studies from the La Jolla Institute for Immunology and from the German Charité University Hospital, both of which highlighted the importance of T cells in COVID-19 immunity.

The La Jolla team found that blood samples collected between 2015 and 2018 had helper T cells that detected the SARS-CoV-2, while the German researchers speculated that past infection with a milder human coronavirus could generate an immune response that's strong enough to repel the novel pathogen.