Ancient Mars May Have Had Received Water From Two Major Sources

- Ancient Mars may have received its wealth of water from a couple of major sources, new research suggests.

- Studying the content of Martian meteorites that arrived on Earth revealed different hydrogen isotopes that hint at the planet's watery history.

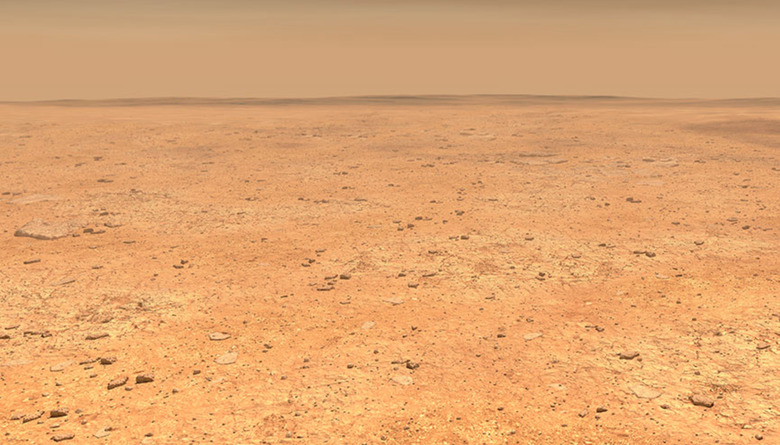

- A small amount of water and ice remains on Mars today, but the planet is believed to have once hosted vast oceans on its surface.

- Visit BGR's homepage for more stories.

Ancient Mars likely received a wealth of water from two primary sources, according to a new study by a team at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. The research, which was published in Nature Geoscience, suggests that Mars' watery past may have been made possible thanks to two large sources.

Scientists have known for some time now that Mars not only still has a little bit of water, but it used to have a whole lot more. In fact, the Red Planet may have once hosted massive bodies of water that could have supported life, but where exactly did it come from?

Studying the history of water on Mars is difficult without actually being there. Thankfully, Mother Nature actually delivered pieces of Mars to Earth in the form of meteorites. Two of these space rocks in particular — the Allan Hills 84001 and the Northwest Africa 7034 meteorites — offered clues that hint at a very interesting past.

"A lot of people have been trying to figure out Mars' water history," Jessica Barnes, lead author of the work, said in a statement. "Like, where did water come from? How long was it in the crust (surface) of Mars? Where did Mars' interior water come from? What can water tell us about how Mars formed and evolved?"

In studying the two meteorites, Barnes and her team noted that they both contained large amounts of different hydrogen isotopes. Called "light hydrogen" and "heavy hydrogen," they hint at two different water sources, and neither rock matches the makeup of the planet's crust. When combined, however, the proportions actually work out nicely. "It turns out that if you mix different proportions of hydrogen from these two kinds of shergottites, you can get the crustal value," Barnes explains.

This suggests that Mars received large amounts of water from two sources. Knowing exactly what they were is, at this point, close to impossible, but an event in which two large chunks of material collide to eventually form a planet is entirely possible. If this is what happened to form Mars, it would explain the differences in the martian meteorites.

"These two different sources of water in Mars' interior might be telling us something about the kinds of objects that were available to coalesce into the inner, rocky planets," Barnes says. "This context is also important for understanding the past habitability and astrobiology of Mars."