NASA's Exoplanet Hunter Just Spotted A 'Super Earth' Orbiting A Nearby Star

In its 15 months of service, NASA's TESS exoplanet-hunting satellite has racked up many exciting exoplanet discoveries, but few show promise in the search for extraterrestrial life. Most of the new worlds are either too hot or too cold — or are composed primarily of gas rather than rock — and are unlikely to support life as we know it.

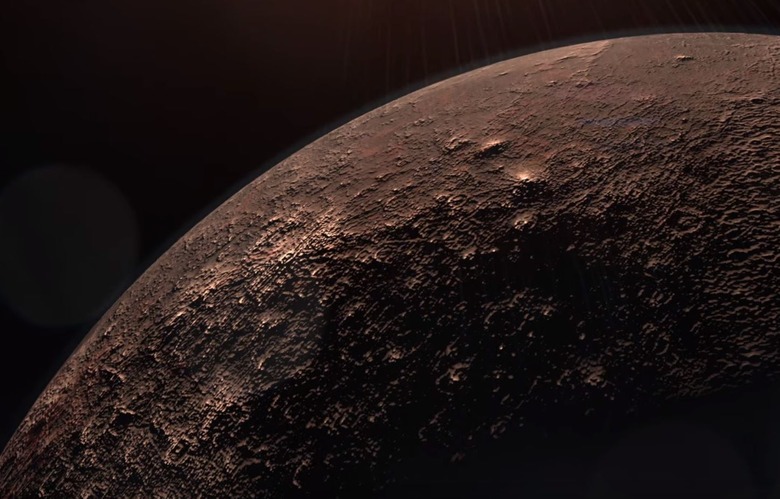

However, a newly-discovered planet orbiting a star close to Earth is one of the rare exceptions, and it's showing some serious promise for researchers to who dream of finding life in space. The planet, called GJ 357 d, is significantly larger than Earth, but may have what it takes to support liquid water on its surface, dramatically increasing its potential to foster life.

Researchers studying the star GJ 357 were trying to confirm the existence of its first-discovered planet, GJ 357 b, when they noticed two other planets orbiting the same star.

GJ 357 b is being called a "hot Earth," meaning that it's rocky and roughly Earth-sized, but far too close to its star to host life as we know it. The more distant of the two additional planets discovered by astronomers, GJ 357 d, would be much more comfortable, and if it has a suitable atmosphere it may be a lot like Earth.

"GJ 357 d is located within the outer edge of its star's habitable zone, where it receives about the same amount of stellar energy from its star as Mars does from the Sun," Diana Kossakowski of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, co-author of a paper describing the new planets, said in a statement. "If the planet has a dense atmosphere, which will take future studies to determine, it could trap enough heat to warm the planet and allow liquid water on its surface."

Liquid water, scientists believe, is crucial for life to take root, but even if the newly-discovered "super Earth" has liquid water that doesn't necessarily mean it's guaranteed to support life. Scientists can only theorize what conditions resulted in life forming on Earth, and search for what they think is the right combination of ingredients.

GJ 357 sits around 31 light-years from Earth, which is closer than many of the stars known to host exoplanets. Still, we'll have to study it from afar for now, as we don't really have any way of getting closer.