T-Mobile Just Spent $8 Billion To Get Signal Across The Entire Country

T-Mobile: great prices, meh coverage. That's been the general consensus for years, but things are about to change in a massive way.

The results of the FCC's low-band spectrum auction just came out, and T-Mobile is the biggest spender by a country mile. The carrier spent $8 billion to buy 45 percent of the available spectrum, including some kind of low-band coverage in every region in America. This is a big win for T-Mobile, and assuming the company can make effective use of the spectrum, Verizon and AT&T just lost their last advantage in network quality.

Dish and Comcast, two companies you don't normally associate with cell phones, were the two other big spenders in this auction. Dish spent a painful $6.2 billion on licenses, and Comcast spend $1.7 billion. Dish provides TV and internet over satellite, so it might be planning some kind of wireless home internet solution using 5G technology and its new spectrum. Who knows.

Comcast, on the other hand, just launched its own wireless service Xfinity Mobile, which uses Verizon's towers to sell service to Comcast TV or home internet customers. It doesn't have enough nationwide coverage to build out an entirely new network only using the licenses it just picked up, but it could be a piece of the puzzle.

What is spectrum anyway?

To understand what's going on, you need to know what spectrum is and who owns it. The wireless radios in your cellphone use different frequencies to communicate with cell towers, depending on what region you're in and which cell carrier you're on. The carriers own the right to use different frequencies (called "bands") in different areas, which keeps networks from interfering with each other. The right to use a certain frequency in a certain area is a license, and it's bought from the government, via the Federal Communications Commission.

But not all frequencies are equal. Lower-frequency signals travel much better over distance, and penetrate buildings much better. The older networks, particularly Verizon and AT&T, own much more low-band spectrum than the newer T-Mobile and Sprint, which is a huge part of why Verizon and AT&T's cell signal has historically been better.

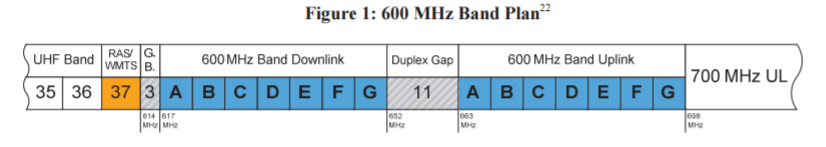

It's not just about which frequency you own, but how much of it you have. In this particular auction, the FCC was selling frequency in the 600MHz range (from 614-698MHz) cut up into bands. Each band has 5MHz of upload and 5MHz of download capacity, with seven total bands available. Each band is available for each major region — so, for example, T-Mobile could buy Band A-C for use in Washington, but Verizon could buy the same chunk of spectrum to use in NYC.

Where did the spectrum magically come from?

The FCC auction wasn't just about selling brand-new spectrum that no one was using: it actually involved buying old spectrum from over-the-air TV stations that weren't using it efficiently, repackaging everything, and then selling the newly-freed-up spectrum to wireless carriers. It was a long and tedious process, and it isn't nearly done yet.

So is my signal getting way better?

Yes — eventually. Because the FCC has to move TV stations around, and the networks need time to test equipment, this process is going to take years. The first TV stations will only be moved in November 2018, so you're looking at a two to three year delay until all this glorious new spectrum comes online.

Will my region be getting service?

The FCC has published the raw results of the new spectrum auction here; you can search by market name, which will likely be your nearest big city, to see which wireless carrier bought spectrum where. If you want to know whether T-Mobile bought up spectrum in your region, or how much, T-Mobile has made a map to show you. The areas with deeper pink are the ones where T-Mobile bought more bands, so will be able to build a higher-capacity network capable of handling more customers at the same time.

Who gets the money?

About $19 billion was spent by all the companies bidding on the new spectrum. Much of that — around $11 billion — is going to the TV stations to pay them for selling their spectrum back to the FCC in an earlier auction. The rest that's left over, nearly $8 billion, goes to the federal government to reduce the budget deficit.