New Study Suggests Certain Memories May Drift In The Brain

Scientists have been working to decode the magic of the human brain for decades. Despite everything that we've learned over the years, there are still new discoveries to be made. And now, a new study that digs deeper into how memories work may have revealed a startling discovery: not all memories stay in one place. Some seem to drift around.

According to a new study featured in the journal Nature, memories tied to places — known as spatial memories — aren't just relegated to any specific cell groups, as scientists previously thought they were. The new research builds off previous findings that suggest cells known as "place cells" aren't the only place that spatial memories are stored. Unlike the previous research, though, this new study sought to knock off many of the variables from the original experiment, something that was only possible thanks to new technologies.

The research has currently only been tested in mice, but it offers an intriguing view into how memories work as a whole and could drive future research to dig even deeper.

Culling the variables

Part of what makes the new research so compelling is the work that the scientists put into removing as many of the variables as possible. Instead of testing how mice moved in a maze they'd revisited time and time again, the researchers utilized a treadmill surrounded by screens to help ensure the mice were moving at the exact same speed each time they ran the experiment.

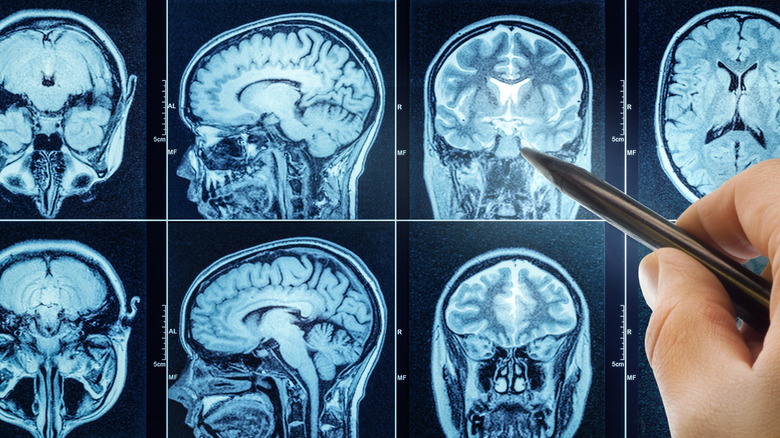

Further, the researchers equipped the mice with a cone that pumped the same scent into their noses each time. This helped ensure that the experience was as close to the same each time the mice underwent it. The researchers also used a substance that made brain cells glow when activated to see what cells activated when the memories were triggered. This allowed them to physically monitor the way the mice's brains worked and provided some compelling results as to how memories related to places are stored.

Instead of seeing the same cells lighting up in the hippocampus each time, the researchers saw that different strings of cells appeared to trigger throughout the experiments. These findings could also line up with the belief that not all memories are stored in the brain. Daniel Dombeck, one of the senior authors on the study, told LiveScience that he believed controlling the experiment so closely would show less drift in the memories. But that wasn't the case at all.

Mice and human brains aren't the same

Despite the findings here, research in mice isn't always guaranteed to apply to humans. Sure, we use mice as a testing subject for a lot of different research that eventually goes on to human-driven trials. But, we still need that human element to see exactly how it applies to our species. And, considering the things we keep discovering about the brain — like the fact the brain doesn't learn how scientists thought — we'll need to see human-based results to see if our memories drift, too.

Perhaps future research can take a look at exactly how memories are stored in the human brain, and determine if we see the same types of drift that scientists have reported in mice. Of course, culling all the variables then will be a bit more difficult, though modern technologies like virtual reality and augmented reality could help scientists create a stable environment for testing.